27 Mar 2024 Getting to grips with Gut Health – Part 1

A healthy gut microbiome is the secret to your wellbeing. Are you ready to design a menu that will lead you there?

You might be wondering why nutritionists are obsessed with gut health. What is all the fuss about and why does gut health matter?

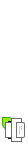

Perhaps it is because virtually every health condition could be improved with a better gut microbiome. Most of us will jump to gastrointestinal diseases when drawing a link between our gut microbiome and health outcomes. But clinical trials have shown remarkable evidence of how diverse beneficial bacteria in our gut can have a positive impact on everything from skin health and fertility (in both men and women), to metabolic syndrome, obesity, autoimmune conditions, cardiovascular disease, cancer, depression and other neuropsychiatric conditions, diabetes and autism.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

So why aren’t we capitalising on this more with simple dietary changes?

The evidence is incredible. One small study for example showed how after only one week of eating foods high in sugar and low in fibre, 16 healthy subjects showed gastrointestinal symptoms and symptoms associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. This sort of eating pattern in such a short space of time also showed a reduction in microbial diversity in the small intestine and increased permeability of the epithelium, the thin layer of tissue that protects our gut. The symptoms were alleviated after discontinuing the diet for seven days. [7]

Seven days! Isn’t that wild? It’s remarkable to think how quickly we can do damage to our gut, but equally how easily we can begin to modify and influence our gut microflora in a positive way if we make small, consistent and sustainable changes.

Despite the compelling evidence that highlights the connection between what we eat and our health outcomes, it is important to acknowledge that reprogramming our gut microbiota can be challenging. The microbiome whether it is healthy or dysbiotic, often exists in a stable state, and so it can be resilient as well as resistant to change even in the face of dietary interventions and antibiotic usage. Scientists are exploring how this gut “memory” can be reshaped through longer-term studies and promising interventions such as fecal transplants.[8][9]

Understanding the gut microbiome

The gut is almost its own little planet, populated with an estimated 100 trillion bacteria, yeasts, fungi and viruses; microbes which form the gut microbiome.

But what does a healthy gut microbiome look like and what does it actually do?

Microbiome populations exist wherever our bodies come into contact with the external environment. So while the gut microbiome is often most talked about and well known, particularly because it is the home of the largest concentration of microbiota, we also have distinct microbial communities in the oral, nasal, male and female reproductive tracts, and also on our skin.

Our microbiome has important functions which include protecting us from pathogens, developing and shaping our immune system, assisting with digestion and absorption of food and supplying energy and nutrients both for us as hosts and for the microbes themselves.[10][11]

A healthy gut microbiome helps to maintain the tight junctions of our epithelial wall. Think of it like a fortress, preventing invaders (toxins) from entering and later exiting through the bloodstream where they can wreak havoc across the body. A lack of diversity in our gut microbiome can weaken the fortress, allow invaders through and promote autoimmune conditions, such as coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease.[12]

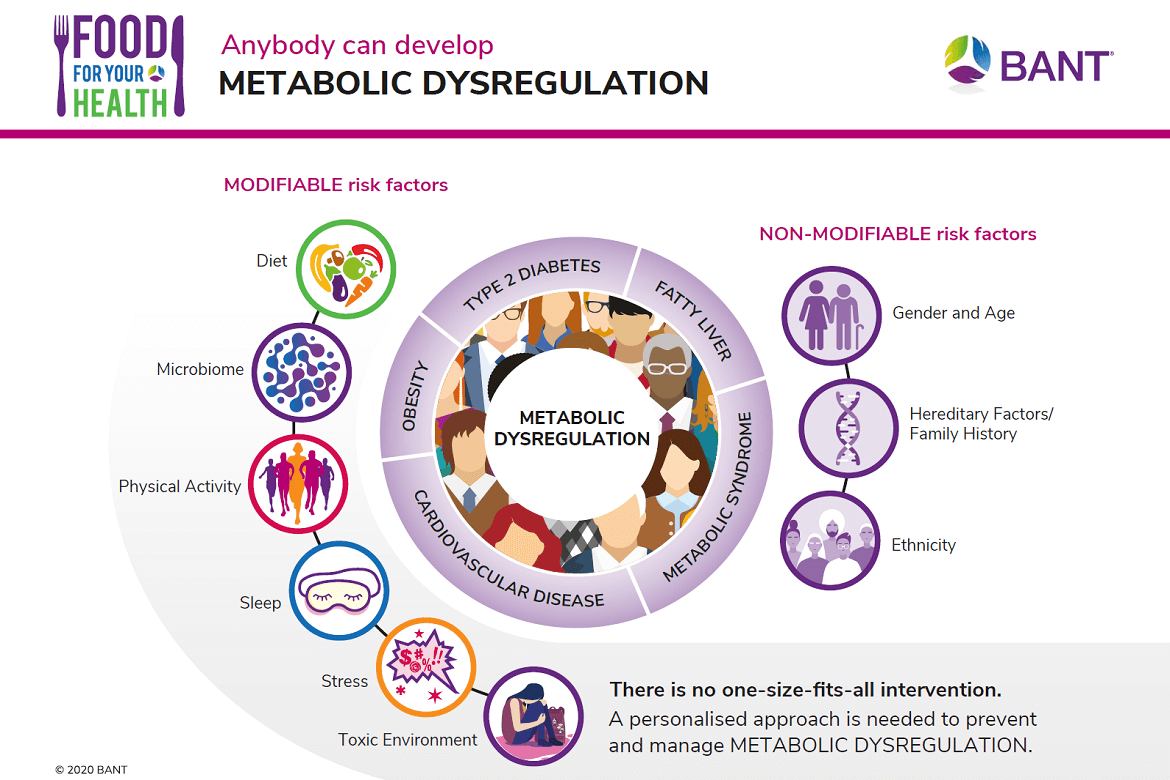

Like our health, the composition and status of our gut flora is constantly changing and evolving, influenced hugely by what we eat, but also by the microbiome of our parents, pets and other animals, environment (geographical location as well as rural versus urban settings), stress, smoking, antibiotic use, certain medications, exercise, lifestyle and more.[13][14][15][16][17][18]

What we choose to eat every day has a profound impact on our microbiome and overall health outcomes.[19][20] It may be more challenging to control where we live, manage our stress or regulate our sleep, but we can alter our dietary patterns to influence how our microbiota survive and thrive.

The development of our microbiome begins at birth. Babies born through the vaginal canal have a high percentage of lactobacilli in their microbiome which indicates the high level of this particular microbial species in the vagina. Babies born via C-section have depleted levels of this bacteria to begin with, but their gut flora can be cultivated at a later stage. In early stages of development, the microbiome lacks diversity, but by the age of around 2.5 years, the makeup, diversity and working capacity of a child’s microbiome (especially those who have been breastfed) begin to look much like the adults around them.[21]

Once infants are able to savour the delights of solid foods, their microbiome goes through a tremendous transformation, heavily influenced by each new ingredient they ingest.

It is crucial to note the incredible variation and individuality of the gut microbiome across populations[22] depending on one’s living arrangements, religious and dietary restrictions, whether you live in a traditional or industrialised society, and so on. For example, the microbial composition of someone with a heavy meat-based diet will look very different from that of someone with high plant-based eating patterns, while those living in a more rural setting may have a richer microbiome than those based in an urban environment.[23][24]

Sidebar 1

While we can acknowledge the huge variation in microbiome compositions across geographies, The Human Microbiota Project discovered that the adult human gut shares some similarities. Around 60% of the gut bacteria is thought to be of the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes type with Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, Clostridium, Escherichia, Streptococcus, and Ruminococcus among the most commonly found species among healthy adults in a Western population.[25]

The point is, there is huge diversity in how we eat globally[26], and thus there is no perfect diet. However, if we look broadly at the macro- and micronutrients that are considered beneficial, we can certainly find ways to develop eating habits that are both culturally familiar and able to enrich our microbiome.

Let’s focus first on the food that will nourish our gut (and explore what may cause damage further down in this article).

Plant power

Plants are perhaps the most important food to eat abundantly to cultivate diverse, beneficial gut flora.

Rich in carbohydrates, plant foods such as sweet potato, corn, blueberries, lentils and squash, which break down into starches and sugars, are metabolised and absorbed in the small intestine. These are digestible carbohydrates.

Indigestible carbohydrates such as oats, barley, quinoa, beans, kale, pears and walnuts, which are rich in dietary fibre, make their way to the large intestine where they are fermented by gut microbes to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

SCFAs supply energy to the epithelial cells and provide approximately 10% of our energy overall each day. SCFAs help keep our gut junctions tight so that pathogens and other unwanted substances have a difficult entry into our bloodstream while nutrients are absorbed. Emerging research also points to the potential of SCFAs in maintaining balanced blood sugar levels, preventing weight gain, reducing inflammation, regulating our immune system, protecting the cardiovascular system, liver and nervous systems.[27][28]

Plant-derived foods are also high in polyphenols, another nutrient component associated with prebiotic and bifidogenic activity. Found in vegetables, fruits, cocoa, tea, coffee and red wine, polyphenols are a class of food that exhibit numerous advantages including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial and neuroprotective qualities.[29] In addition, polyphenol-rich foods such as pomegranates, grapes, ginger, almonds and blueberries have also been shown to aid in increasing the beneficial species of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in the gut, while reducing the pathogenic species Clostridium.[30]

As with indigestible carbohydrates, the vast majority of polyphenols are broken down and digested in the large intestine. Not only can polyphenols increase the amount of various microbial species, but gut microbes in turn can improve the absorption of polyphenols, making them more bioavailable.[31][32]

Clinical trials offer evidence to support a diet rich in plant fibres and polyphenols. A study of 1,135 people from a Dutch population revealed that microbial diversity increased with a higher consumption of fruit, coffee, vegetables and red wine and to a smaller extent drinking tea and eating breakfast. By contrast, microbial diversity was compromised when more carbohydrates, sugar sweetened beverages, bread, beer and savoury snacks were consumed.[33]

Taking all of this into consideration, it is unsurprising that the Mediterranean diet is frequently referenced as an ideal template for healthy eating.[34]

Characterised by colourful fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, fish and olive oil, the Mediterranean way of eating is plentiful in plant fibres, polyphenols and healthy fats, all the ingredients necessary for a healthy gut microbiome. Following this diet can increase Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Prevotella species as well as the production of SCFAs.[35]

Healthy sources of omega 3-fatty acids also form a key component of the Mediterranean diet in the form of olive oil, oily fish, flaxseeds and walnuts. These fatty acids interact with our microbiome in a positive way, helping to restore a balanced and healthy microbial composition leading to a higher production of butyrate, the anti-inflammatory SCFA.[36][37]

Healthy sources of omega 3-fatty acids also form a key component of the Mediterranean diet in the form of olive oil, oily fish, flaxseeds and walnuts. These fatty acids interact with our microbiome in a positive way, helping to restore a balanced and healthy microbial composition leading to a higher production of butyrate, the anti-inflammatory SCFA.[36][37]

Clinical data in preliminary studies also reveal the importance of fermented foods in building a healthy, robust and diverse gut microbiome.[38][39][40] A six-week intervention by scientists at Stanford University found that regular intake of fermented foods decreased inflammatory markers and increased microbial diversity.

The results were surprisingly more pronounced in the fermented food group than in the high-fibre group intervention, especially since the former did not alter other facets of their diet. The researchers posit that to see significant microbial change in the high-fibre group, perhaps a longer period of intervention may be required. Nevertheless, they did note an increase in microbial protein density in stool samples of the high-fibre group and altered SCFA production, suggesting that microbiome modification was occurring, just not necessarily through an increase in the total number of species.[41]

Sidebar 2

Despite the globalisation of food and growing availability of western-style convenience foods, populations and diasporic communities around the world eat very differently depending on their cultural practices and access to ingredients. But the Mediterranean diet can easily be adapted across regions with vibrant, colourful plant-based foods as a priority.

Plant-rich, gut-loving foods around the world

| China | Pak choi, mustard greens, water spinach, lotus root, choi sum, bitter melon, cabbage, mangosteen, bottle gourd, lychee |

| Finland | Blueberries, bilberry, lingonberry, nettle, dill, barley, mushrooms, potatoes, beetroot, turnip |

| India | Aubergine, fenugreek leaves, turmeric, ginger, custard apple, cauliflower, jackfruit, pomegranate, black plum, drumstick |

| Korea | Kimchi, beansprouts, spinach, radish, seaweed, perilla leaf, sweet potato, fern bracken, yuzu, persimmon |

| Lebanon | Sumac, za’atar, olives, lemons, bulgar, loquats, mulberries, figs, Mograbieh pearls, freekeh |

| Mexico | Corn, coriander, black beans, pineapple, ancho chilli, nopal cactus, avocado, mango, jicama, chayote |

| Morocco | Dried apricots, parsley, dates, pumpkin, ras al hanout, harissa, couscous, chickpeas, mandarins |

| Nigeria | Plantain, yam, dandelion greens, amaranth, baobab, bitterleaf, guava, star apples, velvet tamarind, okra |

| Thailand | Lemongrass, galangal, limes, papaya, pomelo, coconut, durian, dragonfruit, morning glory, pandan leaf |

| UK | Parsnips, Brussel sprouts, green peas, fennel, strawberries, butternut squash, blackberries, leeks, rhubarb, apples |

Sidebar 3

How to build a healthy gut*

| Foods my gut will love | Where to find them? | Why is it important? |

| Plants | Carrots, celery, cucumber, aubergine, peppers, broccoli, pak choi, cauliflower, ginger, garlic, kale, peas, bitter gourd, shiso, beansprouts, lemons | Excellent sources of fibre to help cultivate short-chain fatty acids in the gut. Rich source of flavonoids and antioxidants to reduce inflammation |

| Fermented food | Sauerkraut, kimchi, yoghurt, kombucha, kefir, fermented vegetables, tempeh, miso, idli | Helps reduce gastrointestinal intolerance symptoms and cholesterol, improve insulin sensitivity and increase beneficial gut bacteria[42][43] |

| Polyphenols | Fruits, such as mango, banana, apple, grape and durian; seeds such as sunflower, sesame and pumpkin; cocoa; red wine; and tea | Contributes to microbial diversity, reduces pathogenic species, and could help prevent the onset of type-2 diabetes[44][45] |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | Salmon, mackerel, anchovies, sardines, herring, flaxseeds, linseeds, walnuts, olive oil | Contributes to microbial abundance. Can help produce anti-inflammatory compounds such as short-chain fatty acids, and help maintain the integrity of the gut lining. Also contributes to the health of the gut-brain axis.[46][47] |

* This list is not exhaustive!

In part 2, we’ll take a look at dysbiosis and factors affecting the gut microbiome and leading to disease.

Author:

Vandana Chatlani, BANT Registered Nutritionist ® NT Dip, mBANT, rCNHC

NOTES TO EDITORS:

BANT is the leading professional body for Registered Nutritional Therapy Practitioners in one-to-one clinical practice and a self-regulator for BANT Registered Nutritionists®. BANT members combine a network approach to complex systems, incorporating the latest science from genetic, epigenetic, diet and nutrition research to inform individualised recommendations. BANT oversees the activities, training and Continuing Professional Development (CPD) of its members.

Registered Nutritional Therapists are regulated by the Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council (CNHC) that holds an Accredited Voluntary Register (AVR) for the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA). A report by the Royal Society for Public Health and the Professional Standards Agency made a key recommendation that AVR practitioners have the authority to make direct NHS referrals, in appropriate cases, to ease the administrative burden on GP surgeries. BANT nutrition practitioners are the key workforce asset to harness 21st century lifestyle medicine to tackle the rising tide of stress-related fatigue, obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, dementia and other chronic diseases.

To find a BANT nutrition practitioner, please click here

BANT WELLBEING GUIDELINES:

The BANT Wellbeing Guidelines are specifically designed to provide clear, easy to understand general information for healthy diet and lifestyle when personalised advice is not available.

BANT launched it’s 2021 Food for your Health campaign to tackle diet-induced obesity and metabolic dysregulation and combat the junk food culture by promoting healthy food and lifestyle choices. We offer a range of free, open-access resources, and have a network of over 3,500 Nutrition Practitioners throughout the UK.

References:

[1] Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9311318/

[2] The microbiome and human cancer, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8767999/

[3] The Microbiome, an Important Factor That Is Easily Overlooked in Male Infertility, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.831272/full

[4] Environmental factors, gut microbiota, and colorectal cancer prevention, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6314893/

[5] Association between gut microbiota and psychiatric disorders: a systematic review, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10435258/

[6] The links between gut microbiota and obesity and obesity related diseases, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S075333222200066X

[7] Small intestinal microbial dysbiosis underlies symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6494866/

[8] Huberman, A., (Host). Huberman Lab, (2021-present). Dr Justin Sonnenburg: How to Build, Maintain & Repair Gut Health [Audio podcast]. Scicomm Media.

[9] Effect of Diet on the Gut Microbiota: Rethinking Intervention Duration, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6950569/

[10] Part 1: The Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4566439/

[11] Introduction to the human gut microbiota, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5433529/

[12] Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5440529/

[13] Introduction to the human gut microbiota, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5433529/

[14] Huberman, A., (Host). Huberman Lab, (2021-present). Dr Justin Sonnenburg: How to Build, Maintain & Repair Gut Health [Audio podcast]. Scicomm Media.

[15] The Gut Microbiome and Digestive Health – A New Frontier, https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(18)31205-9/fulltext

[16] Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6682904/

[17] Urbanization Reduces Transfer of Diverse Environmental Microbiota Indoors, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00084/full

[18] Analysis of the Gut Microbiome of Rural and Urban Healthy Indians Living in Sea Level and High Altitude Areas, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-28550-3

[19] Diet and the Human Gut Microbiome: An International Review, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32060812/

[20] Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5385025/

[21] Introduction to the human gut microbiota, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5433529/

[22] Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3577372/

[23] Food Components and Dietary Habits: Keys for a Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6835969/

[24] Huberman, A., (Host). Huberman Lab, (2021-present). Dr Justin Sonnenburg: How to Build, Maintain & Repair Gut Health [Audio podcast]. Scicomm Media.

[25] Structure, Function and Diversity of the Healthy Human Microbiome, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3564958/

[26] Diet and the Human Gut Microbiome: An International Review, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7117800/

[27] Health Benefits and Side Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids, https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/11/18/2863

[28] Intestinal Short Chain Fatty Acids and their Link with Diet and Human Health, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00185/full

[29] Dietary Polyphenol, Gut Microbiota, and Health Benefits, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9220293/

[30] Polyphenol supplementation benefits human health via gut microbiota: A systematic review via meta-analysis, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464620300530

[31] Relationship between phenolic compounds from diet and microbiota: impact on human health, https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/143113/4/Relationship%20between%20phenolic%20compounds-Vald%C3%A9s%20et%20al.pdf

[32] Polyphenol supplementation benefits human health via gut microbiota: A systematic review via meta-analysis, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464620300530#b0330

[33] Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5240844/

[34] Food Components and Dietary Habits: Keys for a Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6835969/

[35] Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5385025/

[36] Food Components and Dietary Habits: Keys for a Healthy Gut Microbiota Compositio, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6835969/

[37] Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on the Gut Microbiota, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5751248/

[38] Does Consumption of Fermented Foods Modify the Human Gut Microbiota? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7330458/

[39] Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9003261/

[40] Effects of Fermented Food Consumption on Non-Communicable Diseases, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9956079/

[41] Gut Microbiota-Targeted Diets Modulate Human Immune Status, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9020749/

[42] Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5385025/

[43] Wolf, J., (Host). ZOE Science & Nutrition, (2022-present). Inflammation and your gut: Expert guidance to improve your health [Audio podcast]. Zoe.

[44] Dietary fruit and vegetable intake, gut microbiota, and type 2 diabetes: results from two large human cohort studies, https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-020-01842-0

[45] Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5385025/

[46] Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on the Gut Microbiota, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5751248/

[47] Gut Microbiota Richness and Composition and Dietary Intake of Overweight Pregnant Women Are Related to Serum Zonulin Concentration, a Marker for Intestinal Permeability, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022316623006958?via%3Dihub