21 Nov 2023 Combatting Stress with a Nutritional Approach

How to avoid feeling floored by chronic stress!

The feeling of stress is familiar and manifests itself in plentiful ways. We feel stress when we’re sandwiched between commuters at rush hour, trying desperately to calm a screaming toddler, or competing in a race.

Stress plays a part in our daily existence and is a key component of our survival armour

Initially, the stress response is adaptive and helps prepare our bodies to cope with an onslaught of stressors that are both internal (fears and anxiety, for example) and environmental (financial struggles and pollution).

Our stress response is principally governed by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Stress activates the HPA axis and starts a domino of neuroendocrine signals which trigger the release of hormones and neurotransmitters such as cortisol, noradrenaline, and adrenaline.

Learning to understand and accept acute stress; stress which occurs over a short period of time, can potentially be helpful to us, as it equips us to deal with stressors later in life. A stress response in this case is protective and could even work as a motivating factor. We deal with the stressor, make a quick recovery, and soon return to a state of homeostasis or equilibrium – balanced and calm.[1]

By comparison, repeated or prolonged acute stress, which fast transforms into chronic stress, can deplete our resources to the point of damaging our health.

Global conflicts, domestic violence, working multiple jobs and caring for someone with a chronic illness are all examples of this type of persistent, intensive stress, which can compromise health. In these cases, the stress response is continuously activated. The stressor, like a champion boxer in a ring, pummels our neuroendocrine and immune systems to the ground. They fight the stressor, actively defend the body from physical dangers and pathogens, and attempt healing and cell repair. But if the stressor repeatedly throws punches and proves too strong, our neuroimmune axis cannot sustain the blows, our reserves run dry, and eventually we get knocked out.[2]

Such overstimulation causes a maladaptive stress response with fatigue and immune imbalances that result in chronic low-grade inflammation. This heightened state of stress can contribute to the development of cardiovascular dysfunction, cancer, cognitive disorders, diabetes, autoimmune conditions, and impaired mental health.[3][4][5]

When our stress response is overstimulated, our bodies can no longer produce appropriate amounts of cortisol, a hormone which plays a major role in our stress response. We may produce too much cortisol at night, disrupting our sleep patterns, and not enough in the morning which leads to fatigue and a poor circadian rhythm overall. This is one sign of excessive stress and is linked to a number of symptoms such as morning exhaustion even following a restful night, energy dips in the afternoon, low libido, poor memory, salt cravings, and skin rashes, among others.

When our stress response is overstimulated, our bodies can no longer produce appropriate amounts of cortisol, a hormone which plays a major role in our stress response. We may produce too much cortisol at night, disrupting our sleep patterns, and not enough in the morning which leads to fatigue and a poor circadian rhythm overall. This is one sign of excessive stress and is linked to a number of symptoms such as morning exhaustion even following a restful night, energy dips in the afternoon, low libido, poor memory, salt cravings, and skin rashes, among others.

Clinicians and patients attribute a combination of these symptoms to adrenal fatigue which is related to low cortisol and HPA dysfunction. HPA dysfunction is frequently associated with emotional and psychological stress, high and low blood sugar, irregular and disturbed sleep patterns, and inflammation caused by a sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, digestive distress, depressed mood, decreased productivity, and other factors.

The signs and symptoms of stress vary from one individual to the next and consist of physical, mental, and emotional elements. While some typically report fatigue, insomnia, depression, fatigue and headaches, others cite problems such as irritability, digestive disturbances, guilt, sweating and breathlessness.[6]

Stress equally impacts our physical health, leading to symptoms such as raised blood pressure, blood sugar and heart rate. This is down to our primitive brain, which prioritises safety over health in an acute stress state. Think of being in the woods alone and suddenly seeing a grizzly bear. Your brain will trigger a fight-or-flight response activating your sympathetic nervous system. It is highly likely that you will run for your life (flight) but perhaps you’d be brave enough to fight instead. Our stress response in this case is designed to ensure our survival, so in this state, our bodies are primed to face or flee the threat in front of us.

Modern-day stressors such as screen addiction, sleep deprivation and high alcohol consumption, may seem a lot less dramatic than confronting a grizzly bear. But because we routinely indulge in these behaviours, they can trigger and prolong our stress response. Instead of experiencing high blood pressure, a high heart rate, low appetite, poor digestion and other symptoms for a short period to help us escape a threat and recover, these symptoms persist indefinitely, pushing our hormones, immunity and overall stress response mechanism out of kilter. Our bodies divert resources away from our immunity, digestion and wellbeing, our sympathetic nervous system dominates, and our health suffers as a consequence.

Can a nutritious diet help to alleviate stress?

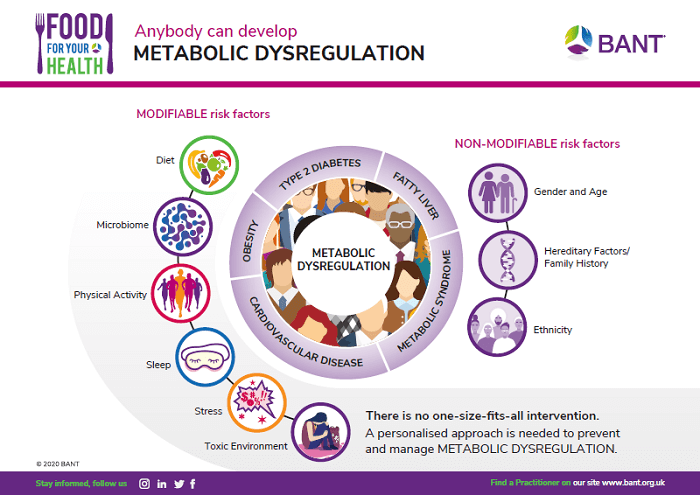

We often think of stress as something external and outside our control. However, stress is a modifiable factor that can be influenced through diet and lifestyle. Our food choices, particularly an inflammatory diet, can easily be the culprit behind elevated stress levels. Research has consistently shown that the conventional Western diet, high in refined carbohydrates, sugar, and saturated fats, and low in whole fruits, vegetables and grains, is inflammatory and detrimental to our wellbeing.[7][8] Studies have observed how eating high-fat meals can elevate the amount of triglycerides and glucose circulating in our blood. When these levels remain high, they can increase our risk of heart risks, type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity. More interestingly, when we are in a heightened state of stress, our bodies can struggle to eliminate the lipids in our blood.

Unfortunately, existing stressors can influence our food choices in a harmful way. We opt for comfort foods to soothe our feelings of stress, but many times that food – high in fat, sugar and salt – fails to nourish us and serves only to deepen our biochemical stress response. Stress negatively affects the action of the vagus nerve – part of the parasympathetic nervous system – which controls our digestion, absorption and metabolism. When vagal nerve activity is dysfunctional, it can lead to disrupted signals that determine hunger and satiety, leading us to overeat and gain weight (adding yet another stressor to the picture). This is why picking nutritiously dense foods is so crucial for us when we are in a heightened state of stress so as not to dysregulate vagal nerve function. Foods such as omega-3 fatty acids, found in salmon, mackerel, anchovies, and sardines, for example, can improve mood and vagal nerve activity.[9][10]

We face internal and external stressors prompted by what we eat, the state of our mental, emotional and physical health, lifestyle choices and our environment. Any physical or psychological stimuli that upsets our equilibrium – our homeostatic state – can create a stress response.

What to eat in a stressful state

Our bodies become depleted in a number of minerals and vitamins during times of stress. Studies have demonstrated how magnesium levels fall in times of stress and how low magnesium can increase the body’s vulnerability to stress. Magnesium is involved in over 300 major metabolic and biochemical processes in our bodies. In stressful times, incorporating foods high in magnesium such as legumes, nuts, wholegrain cereals and fruit, could be beneficial.[11]

Focusing on other minerals such as zinc (poultry, oysters, seafood, nuts, red meat, eggs and dairy), copper, manganese, selenium, molybdenum, chromium and iodine could also be useful as they help support adrenal function. In some cases, a supplement may be more effective than using diet interventions alone.

Because HPA axis dysregulation often wreaks havoc on our blood sugar regulation and insulin secretion, a moderate consumption of carbohydrates along with low refined sugar intake could be beneficial.[12][13][14] Many will suffer from low blood sugar, but sometimes people will have a combination of both low and high levels. Working with a nutritionist to find the right level of carbohydrate consumption is crucial, because inadequate levels can make symptoms such as brain fog, fatigue and sleep disruptions worse.

Because HPA axis dysregulation often wreaks havoc on our blood sugar regulation and insulin secretion, a moderate consumption of carbohydrates along with low refined sugar intake could be beneficial.[12][13][14] Many will suffer from low blood sugar, but sometimes people will have a combination of both low and high levels. Working with a nutritionist to find the right level of carbohydrate consumption is crucial, because inadequate levels can make symptoms such as brain fog, fatigue and sleep disruptions worse.

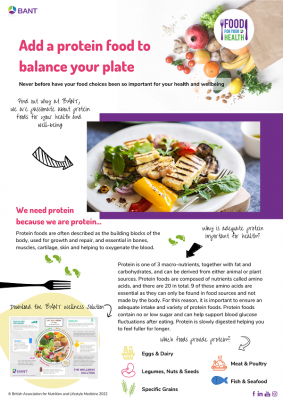

Choosing good sources of protein can also have a positive impact stress on levels through better blood-sugar regulation and improved mood as a result of amino acids such as tryptophan, tyrosine and phenylalanine. These amino acids form the base ingredients for our neurotransmitters, the signalling molecules which can balance our stress response.[15]

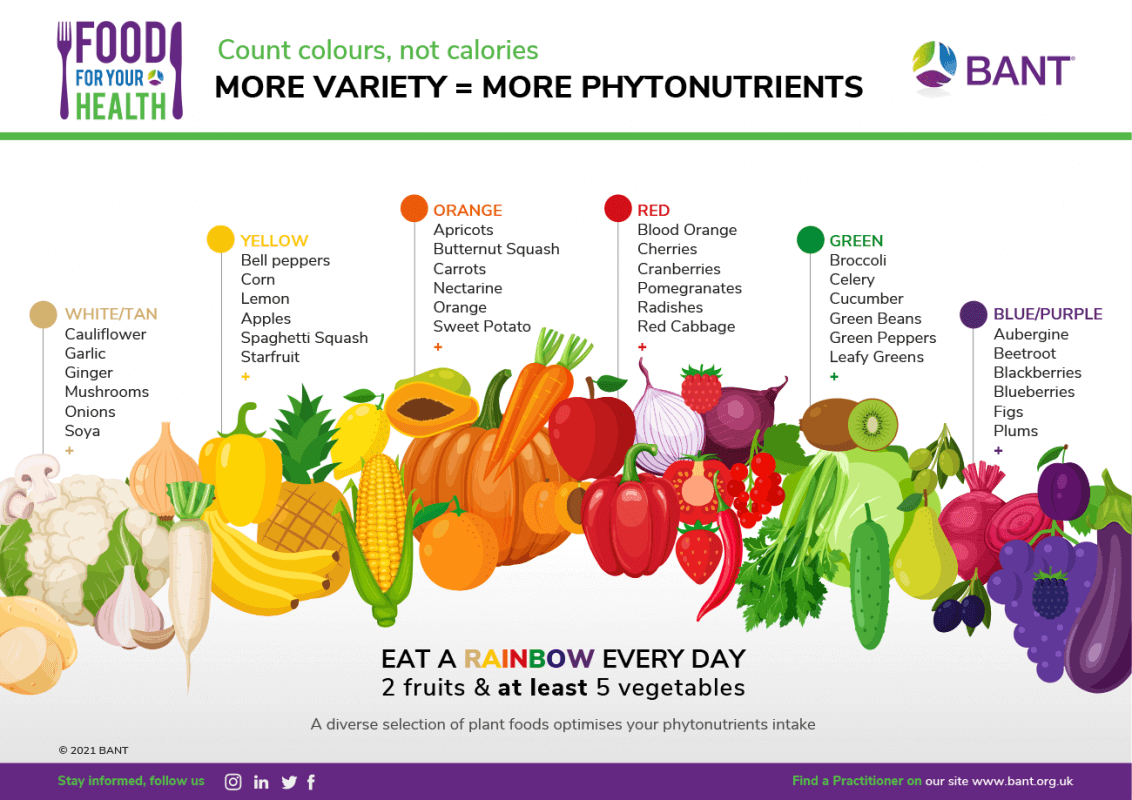

The inclusion of whole foods, particularly fruit and vegetables is a no-brainer because of their high antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties which can moderate our stress response in important ways. Dark green leafy vegetables along with peppers, a variety of fruit, whole grains, and lean meat can help sustain us when our stress levels are at their peak.

Researchers are also looking into the impact of vitamin C supplementation and diet modifications as a means to combat stress since this appears to offer neuroprotective properties. Animal studies have demonstrated how ascorbic acid supplementation can help reduce stress-induced cortisol output.[16] Vitamin C-rich foods such as citrus fruits, berries, kiwis and peppers could be incorporated alongside lifestyle changes to help manage our stress response.

Those in high-stress situations could also profit from reduced caffeine and alcohol consumption which can act as chemical stressors. Caffeine can amplify cortisol production hours after you’ve had your cup of coffee and these levels can remain high when caffeine is consumed regularly. [17][18]

As we covered earlier in this piece, habits and behaviours such as screen addiction and poor sleep can have a drastic effect on our stress response through cortisol secretion. When cortisol levels rise, we are prone to increase our energy intake – often consuming unhealthy foods that give us a quick burst of energy. Maintaining good sleep hygiene is fundamental to combating stress and helping our bodies to rest, replenish and recover.[19]

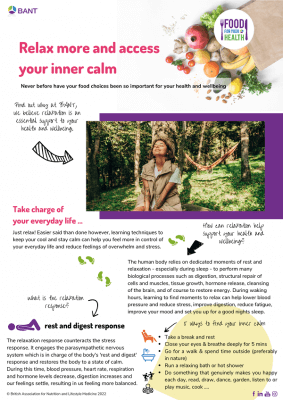

The positive effects of deep breathing, meditation and yoga in stimulating our parasympathetic nervous system have been well-documented. Vagus nerve activity can be enhanced through these lifestyle habits promoting greater resilience to stress while also improving mood and anxiety.[20]

Download our lifestyle guides here.

Author: Vandana Chatlani, BANT Member & Registered Nutritional Therapy Practitioner

———————————————————————————————————————

NOTES TO EDITORS:

BANT is the leading professional body for Registered Nutritional Therapy Practitioners in one-to-one clinical practice and a self-regulator for BANT Registered Nutritionists®. BANT members combine a network approach to complex systems, incorporating the latest science from genetic, epigenetic, diet and nutrition research to inform individualised recommendations. BANT oversees the activities, training and Continuing Professional Development (CPD) of its members.

Registered Nutritional Therapists are regulated by the Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council (CNHC) that holds an Accredited Voluntary Register (AVR) for the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA). A report by the Royal Society for Public Health and the Professional Standards Agency made a key recommendation that AVR practitioners have the authority to make direct NHS referrals, in appropriate cases, to ease the administrative burden on GP surgeries. BANT nutrition practitioners are the key workforce asset to harness 21st century lifestyle medicine to tackle the rising tide of stress-related fatigue, obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, dementia and other chronic diseases.

To find a BANT nutrition practitioner, please click here

BANT WELLBEING GUIDELINES:

The BANT Wellbeing Guidelines are specifically designed to provide clear, easy to understand general information for healthy diet and lifestyle when personalised advice is not available.

BANT launched its “Food for your Health” Campaign in February 2021 to provide open-access resources to help guide the public towards healthier food choices in prevention for diet-induced disease. Download a wide range of food and lifestyle guides, recipes, infographics, planning tools and fact sheets and start ma

References:

[1] Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2568977/

[2] Current Directions in Stress and Human Immune Function, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4465119/

[3] The effects of chronic stress on health: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain–body communication, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5137920/

[4] The Impact of Everyday Stressors on the Immune System and Health, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-16996-1_6

[5] The impact of stress on body function: A review, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5579396/

[6] Stress, https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/feelings-symptoms-behaviours/feelings-and-symptoms/stress/

[7] Association Between Healthy Eating Patterns and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2767106

[8] Diet, Lifestyle, and Genetic Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes: A Review from the Nurses’ Health Study, Nurses’ Health Study 2, and Health Professionals’ Follow-Up Study, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13668-014-0103-5

[9] Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5859128/

[10] Role of the vagus nerve in the development and treatment of diet‐induced obesity, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5063945/

11 Magnesium Status and Stress: The Vicious Circle Concept Revisited, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7442351/#:~:text=The%20largest%20body%20of%20evidence,on%20calcium%20and%20iron%20concentrations

[12] The dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in diet-induced prediabetic male Sprague Dawley rats, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7731754/#:~:text=It%20has%20been%20shown%20that,fats%20%5B61%2C%2062%5D

[13] Stress and eating behaviors, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4214609/

[14] The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, Obesity, and Chronic Stress Exposure: Foods and HPA Axis, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13679-012-0024-9

[15] Impact of a Specific Amino Acid Composition with Micronutrients on Well-Being in Subjects with Chronic Psychological Stress and Exhaustion Conditions: A Pilot Study, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5986431/#:~:text=An%20adequate%20supply%20of%20specific,)%2C%20and%20glycine)%20neurotransmitters%20and

[16] The role of vitamin C in stress-related disorders, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0955286320304915?via%3Dihub

[17] Caffeine consumption and self-assessed stress, anxiety, and depression in secondary school children, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4668773/#:~:text=The%20analysis%20found%20the%20%3E1000,latter%20effect%20was%20not%20significant.

[18] Caffeine Stimulation of Cortisol Secretion Across the Waking Hours in Relation to Caffeine Intake Levels, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2257922/

[19] The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, Obesity, and Chronic Stress Exposure: Foods and HPA Axis, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13679-012-0024-9

[20] Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044/full