21 Jul 2022 Escaping the Junk Food cycle: is it possible?

Are ultra-processed foods and poor-health inevitable companions

National Junk Food Day is celebrated every year on July 21st as a celebration of the foods people like to snack on. Pitched as the ultimate ‘cheat day’, the reality for many, is this is their everyday diet thanks to the ease of accessibility and affordability of these foods. And it is precisely this diet, lacking in the fundamental basics of nutrition, which is contributing to the worsening UK and global obesity rates and rise in non-communicable diseases (namely those you can’t catch but which develop, in-part, because of diet-induced and lifestyle factors). Can we realistically break the junk food cycle or as the cost-of-living crisis worsens are households bound to ultra-processed foods as a means of survival?

We have reached a precipice in the battle to reduce obesity rates and combat the rise in diet-induced illness in the UK. Since 1992, 14 government-led strategies and 680 polices related to obesity have failed, including the current governments 2020 ‘Better Health’ campaign and NHS digital weight management services (1), the funding for which has incidentally now been pulled (2). The cliff-edge we are standing on is that of actively confronting the ‘modifiable causes’ for obesity, not least diet and the plethora of ultra-processed products being marketed by manufacturers. The government commissioned the 2021 National Food Strategy to ask an independent body of experts how to create a more sustainable food system for the health of people and planet. The Dimbleby report provided a masterly study of the UK’s food problem and gave a framework wide enough to be deployed, measured, and continuously assessed across all sectors. Was it perfect? No. But it was certainly better than anything the government has proposed. The government has chosen not to fully engage and instead continues to cling to the cliff-edge, paralysed with procrastination. Why? Because taking that leap of intent would mean acknowledging one of the key elements of the report: that as a nation we are trapped in a junk food cycle, and that the cycle can only be broken by challenging food manufacturers. Instead, the government has chosen to placate industry and delay the ban on junk food TV advertising and BOGOF (buy one get one free) promotions until 2023. It has side-stepped the recommendations to implement sugar and salt reformulation taxes, despite manufacturers asking for legislation as a means of leveling the playing food and safeguarding competition to ensure conscientious manufacturers are not penalised for improving their product formulation should others carry on with existing formulas. . Somewhat perversely, and despite the growing bank of evidence linking ultra-processed foods and drinks to obesity, the government instead wishes to commission an £11 million UKRI-led ‘Diet & Health Open Innovation Research Club’ to further explore the role of ultra-processed foods and health. What do they hope to discover that we don’t already know?

Debates about ultra-processed foods and drinks and their association with obesity is nothing new (3,4,5,6). What has changed is the worsening economic situation and people are understandably worried about food price inflation and the increasing difficulty of affording a healthy diet. Rather than acknowledging this with decisive and positive action, the government is using this as an excuse for their most recent indecisions. After all, how can one ban BOGOFs (buy one get one free) when households are struggling to put food on the table? What they are failing to grasp however, is that this simply fuels greater health disparities and puts more people at risk of obesity and related health conditions. What people want is access to affordable real food, not more junk. The government’s delay tactics are doing little to fix this.

The newly published Food standards Agency (FSA) ‘Our Food 2021’ report says, poor diet causes 13 per cent of all deaths and four times more people are living with obesity compared with 1980, as well as claiming that many teenagers are having about two and a half times more sugar than the recommended maximum intake and gives similarly bleak figures for over consumption of saturated fat and salt (7). Government agencies are themselves highlighting the issues of junk food related diets but a lack of joined-up-thinking across government agencies means this data is not acted upon. Worse still, the government simply proposes to waste more tax-payers money to generate more data.

Let’s take the sugar discussion in isolation. To promote healthier people, we need to prioritise promoting whole food ingredients, and not only mandate band-aid tactics to ‘minimally improve’ processed foods and drinks. That said, the 2018 soft drinks levy which applied a two-tiered tax to all soft drinks containing 5 grams or more of added sugar has led to eight out of the top ten companies reportedly reducing the sugar content of their products by 15% or more (8). What is not clear without mandatory reporting, is whether product reformulation leads to healthier alternatives. Firstly, inconsistencies with the current categorisation of fructose and maltodextrins1 mean manufacturers simply switch from sucrose to fructose and secondly, labelling loopholes allow manufacturers to mislead consumers regarding sources of sugar and modified starches (which currently do not have to be declared as sugar despite having a high GI ranking). The National Food Strategy called for mandatory reporting alongside product reformulation recommendations. It is difficult to see how the government can tax fructose on the one hand but give it a positive health claim as being a good substitute for sucrose, on the other given the evidence (9,10,11,12,13,14). Furthermore, this does little to promote whole food and simply strives to modify junk.

The reality is that the UK is on its way to becoming the fattest nation in Europe! The World Health Organisation (WHO) has predicted the UK will become the most obese nation in Europe by 2030 (15,16). There is overwhelming evidence that obesity is a growing public health crisis across the country with statistics showing 28% of adults in England are obese and a further 36.2% are overweight. Since 1993 the proportion of adults in England who are overweight or obese has risen from 52.9% to 64.3%, and the proportion who are obese has risen from 14.9% to 28.0%. In the most deprived areas in England, prevalence of excess weight (overweight or obese) is 9 percentage points higher than the least deprived areas (17). To quote the National Food Strategy “It’s not just an abundance of food that has caused this landslide. It is also the particular nature of the food”. This sits alongside retail data showing that 50% of the UK basket is comprised of ultra-processed foods and drinks, and that BOGOFs increase purchase of these products by an average of 15 percent (18). Manufacturers know this, as proven by the unsuccessful Kellogg’s legal challenge over promoting their high sugar cereals in prominent positions instore. Some argue that manufacturers should be prepared to show leadership and support government policy however, it is unclear where current government policy stands given the DEFRA white paper response to the National Food Strategy. Who is leading who?

If we cannot rely on government and manufacturers, then surely the solution lies in preventative personalised nutrition and lifestyle medicine? In April 2020 Boris Johnson led a jubilant charge for weight-loss after his release from hospital for COVID-19, acknowledging being overweight contributed to the severity of his illness. However, his ‘Better Health’ campaign was flawed from the beginning. Rather than targeting the multi-factorial causes for overweight and obesity, the campaign followed in the footsteps of commercial weight loss programs by promoting calorie counting over choosing nutrient-dense foods, and by using BMI as the only measure of healthy weight versus more comprehensive body composition biometrics of fat mass, visceral fat, and muscle mass. The campaign went as far as to partner with branded weight loss programs and their ultra-processed ‘weight-loss’ products (all of which stood to gain commercially). These programs and their products are not science-based and typically are run by brand ambassadors with no nutritional qualifications. This, when the UK has an under-utilised and under-recognised workforce of nutrition practitioners, both within the NHS and the private integrated healthcare sector. Furthermore, adherence to these weight loss programs typically relies on individuals replacing meals with shakes and meal substitutes. The issue here being there is no education about how to make healthy food choices and change damaging lifestyle habits. Once individuals return to their ‘normal’ diet the weight creeps back up. Why? Because nothing has fundamentally changed. Once again, a band-aid approach to tackling obesity which delivers limited or no long-term sustainable results. With the cancellation of £100m funding for weight management services pulled in May 2022, this trend is set to continue (19)

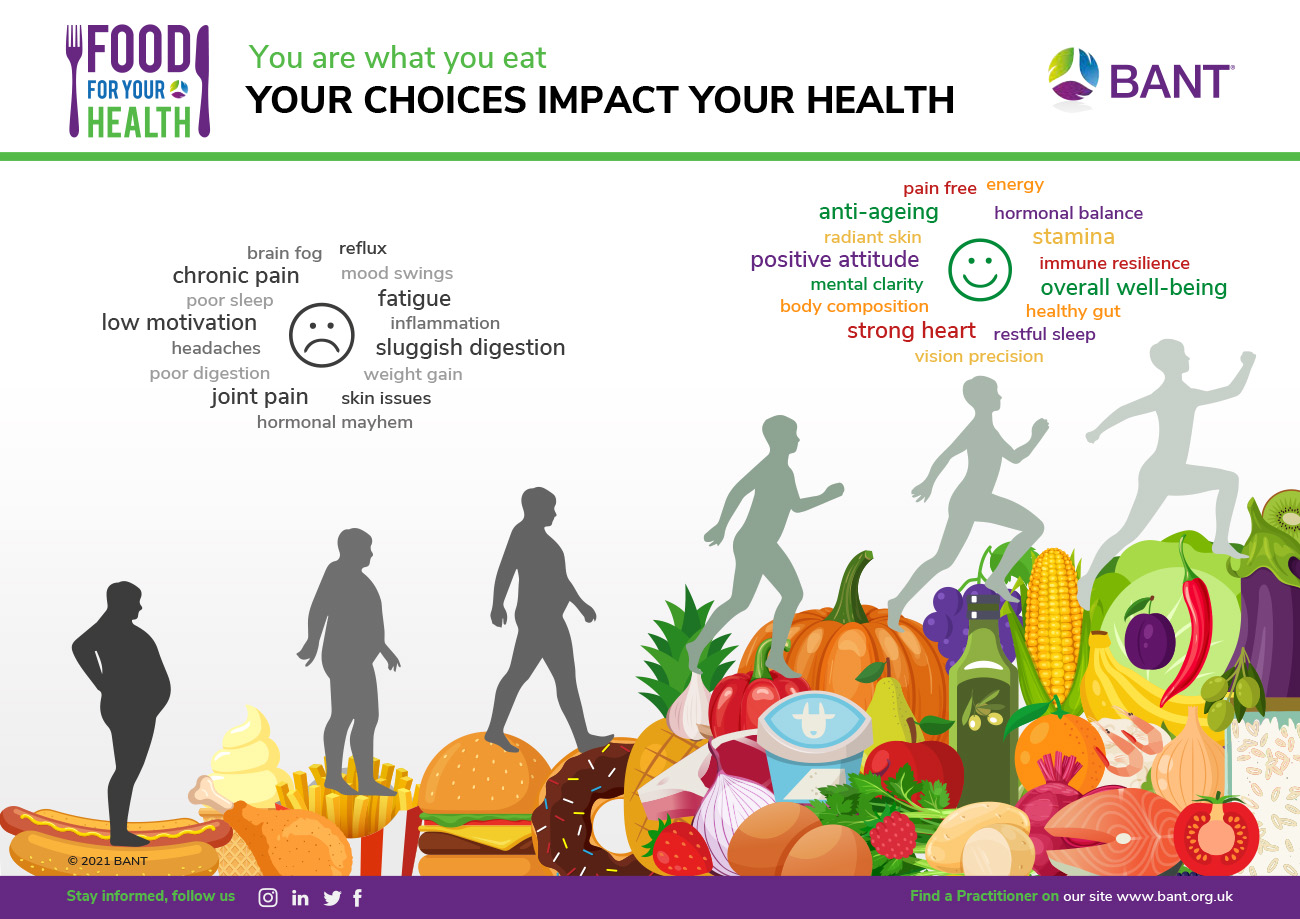

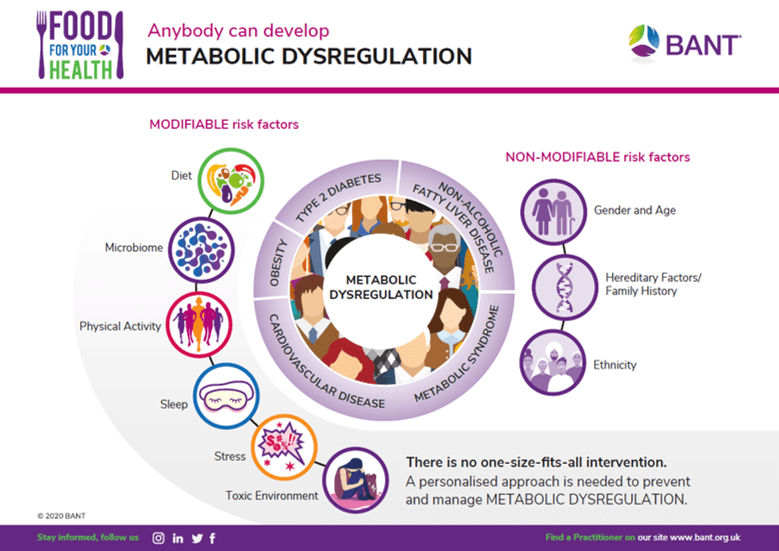

The reasons for obesity are multifactorial and personalised integrated medicine looks at the modifiable factors that an individual can directly influence, which include diet, supporting the gut microbiome, physical activity levels, sleep quality, stress management and environmental causes (see Figure 1). There is also the need to overlay these with socio-economic factors, accessibility, and affordability of healthy food ingredients as no amount of education can inspire individuals to change their diet if the fundamentals of food pricing and health inequalities remain unaddressed. Without tracking back to these root causes of obesity and adopting a prevention-led approach to re-educating individuals on ingredients, diet, nutrition, cooking skills, and lifestyle, all government proposals are destined to fail. Currently only 5% of NHS spending goes towards prevention with 95% on acute care.

The question therefore remains, is it possible to break the junk food cycle or are we destined to become the fattest nation in Europe, come what may?

Encouragingly there is more and more evidence supporting the effectiveness of a personalised integrated nutrition approach versus a one-size-fits-all policy (20,21,22, 23). The upside is that dietary education and behaviour change are embedded in this approach, meaning individuals are more likely to succeed in achieving a healthy weight following recommendations, and maintain that weight longer-term. The downside, is that personalised nutrition and lifestyle medicine is currently in the domain of independent practitioners and not primary health care, meaning those who need these services are the least likely to have financial access to them. Cue social prescribing to integrate GP and community health assets. Absolutely, if those assets include key workforce assets such as Registered Nutritional Therapy Practitioners, on accredited voluntary registers (AVR). BANT’s 3500 practitioner members are required to be registered either with Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council (CNHC) or be statutorily regulated. CNHC holds a register accredited by the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA), an independent body accountable to the UK Parliament. A report by the Royal Society for Public Health and the Professional Standards Agency made a key recommendation that AVR practitioners have the authority to make direct NHS referrals, in appropriate cases, to ease the administrative burden on GP surgeries. This is still not happening.

In March 2022, BANT celebrated 25 years of leading the profession and setting the standards in science-based nutrition and lifestyle medicine. We are seeing signs of a paradigm shift towards more personalised integrative medicine, but we have a long way to go. As long as the UK diet is so reliant upon ultra-processed junk foods, we can expect to see the numbers of non-communicable diseases continue to rise until this, or perhaps the next government, makes some meaningful policy.

Find a Practitioner at www.bant.org.uk

Author: Claire Sambolino MSc, Registered Nutritional Therapy Practitioner, BANT Communications Manager

Explanations:

Maltodextrins1 – Maltodextrins (modified starches). Routinely used to replace fat to achieve lower calorie products, and to replace mono- and di-saccharides, often with artificial sweeteners, because they do not have to be labelled as sugar. Processed starches (calorific maltodextrin) should be flagged as having a high GI ranking.

References:

- https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/britains-obesity-crisis-how-did-we-get-so-big-fcdcchc5z

- https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/954213?src=wnl_newsalrt_uk_210705_MSCPEDIT&uac=297145FR&impID=3487216&faf=1

- Elizabeth L, Machado P, Zinöcker M, Baker P, Lawrence M. Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 30;12(7):1955. doi: 10.3390/nu12071955. PMID: 32630022; PMCID: PMC7399967.

- https://www.bmj.com/company/newsroom/new-evidence-links-ultra-processed-foods-with-a-range-of-health-risks/

- Ultra-processed foods and human health: What do we already know and what will further research tell us? Bernard Srour, PharmD, MPH, PhD Mathilde Touvier, MSc, MPH, PhD, February 03, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100747

- Rauber F, Steele EM, Louzada MLdC, Millett C, Monteiro CA, Levy RB (2020) Ultra-processed food consumption and indicators of obesity in the United Kingdom population (2008-2016). PLoS ONE 15(5): e0232676. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232676

- https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/consolidated-annual-report-and-accounts-2020-21.pdf

- https://www.ndph.ox.ac.uk/news/soft-drinks-levy-shows-success-on-reducing-sugar-intakes#:~:text=In%20April%202018%2C%20the%20UK,or%20more%20of%20added%20sugar.

- Jensen T, Abdelmalek MF, Sullivan S, Nadeau KJ, Green M, Roncal C, Nakagawa T, Kuwabara M, Sato Y, Kang DH, Tolan DR, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Rosen HR, Lanaspa MA, Diehl AM, Johnson RJ. Fructose and sugar: A major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018 May;68(5):1063-1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.019. Epub 2018 Feb 2. PMID: 29408694; PMCID: PMC5893377

- Semnani-Azad Z, Khan TA, Blanco Mejia S, de Souza RJ, Leiter LA, Kendall CWC, Hanley AJ, Sievenpiper JL. Association of Major Food Sources of Fructose-Containing Sugars with Incident Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3(7):e209993. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9993. PMID: 32644139; PMCID: PMC7348689

- Russo E, Leoncini G, Esposito P, Garibotto G, Pontremoli R, Viazzi F. Fructose and Uric Acid: Major Mediators of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Starting at Pediatric Age. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jun 24;21(12):4479. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124479. PMID: 32599713; PMCID: PMC7352635

- Yunker AG, Alves JM, Luo S, Angelo B, DeFendis A, Pickering TA, Monterosso JR, Page KA. Obesity and Sex-Related Associations With Differential Effects of Sucralose vs Sucrose on Appetite and Reward Processing: A Randomized Crossover Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Sep 1;4(9):e2126313. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.26313. PMID: 34581796; PMCID: PMC8479585

- Meng Y, Li S, Khan J, Dai Z, Li C, Hu X, Shen Q, Xue Y. Sugar- and Artificially Sweetened Beverages Consumption Linked to Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases, and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients. 2021 Jul 30;13(8):2636. doi: 10.3390/nu13082636. PMID: 34444794; PMCID: PMC8402166

- Toews I, Lohner S, Küllenberg de Gaudry D, Sommer H, Meerpohl JJ. Association between intake of non-sugar sweeteners and health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ. 2019 Jan 2;364:k4718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4718. Erratum in: BMJ. 2019 Jan 15;364:l156. PMID: 30602577; PMCID: PMC6313893.

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/may/05/obesity-crisis-projections-uk-2030-men-women#:~:text=7%20years%20old-,WHO%20report%3A%2074%25%20of%20men%20and%2064%25%20of%20women,to%20be%20overweight%20by%202030&text=Europe’s%20growing%20obesity%20crisis%20will,years%2C%20health%20experts%20have%20said

- https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/353747/9789289057738-eng.pdf

- https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research- briefings/sn03336/#:~:text=Adult%20obesity%20in%20England,is%20classified%20as%20’overweight

- https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/

- https://www.lgcplus.com/finance/exclusive-government-pulls-100m-grant-for-tackling-obesity-11-04-2022/

- Livingstone, K.M., Celis-Morales, C., Navas-Carretero, S. et al. Personalised nutrition advice reduces intake of discretionary foods and beverages: findings from the Food4Me randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 18, 70 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01136-5

- Empowering consumers to PREVENT diet-related diseases through OMICS sciences (PREVENTOMICS): protocol for a parallel double-blinded randomised intervention trial to investigate biomarker-based nutrition plans for weight loss. Aldubayan, MA, Pigsborg, K, Gormsen, SMO, Serra, F, Palou, M, Mena, P, Wetzels, M, Calleja, A, Caimari, A, Del Bas, J, et al BMJ open. 2022;(3):e051285

- Evaluating the Effectiveness of Nutritional Therapy in the McClelland Teaching Clinic at the University of Worcester, Miranda D Harris and Alison Benbow, Online Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine 2021.

- Diets, nutrients, genes and the microbiome: recent advances in personalised nutrition. Matusheski, NV, Caffrey, A, Christensen, L, Mezgec, S, Surendran, S, Hjorth, MF, McNulty, H, Pentieva, K, Roager, HM, Seljak, BK, et al The British journal of nutrition. 2021;(10):1489-1497