28 Jun 2023 The fight against ultra-processed foods and food labelling loopholes!

Reducing obesity and metabolic disease depends on a return to real food and a culture of nutritious eating. Reading ingredient labels and avoiding marketing traps can empower us to make healthier choices.

But can we escape the junk food cycle?

More than 50% of foods consumed in the UK are ultra-processed according to research. These include packaged breads, breakfast cereals, reconstituted meat products, ready meals, confectionery, biscuits, cakes, pastries, industrial chips, soft drinks and fruit juices (1).

Our current food climate is dominated by ultra-processed foods which fuel metabolic dysregulation through their high fat, salt and sugar content (HFSS). These are pushed by BIG Food; multinational conglomerates that monopolise food production and distribution putting profit ahead of consumer health and wellbeing. As a nation, the UK has become addicted to sickly sweetened food and drinks and highly processed foods that, let’s face it, aren’t really foods at all. Manufacturers are exploiting legal loopholes, an absence of regulation and a lack of political will to fuel the soaring consumption of these products to the detriment of our health. These foods are easy to come by and cheap to buy, but their risks to our health are costly both in personal terms and to the NHS as a whole. Ultra-processed foods have consistently been linked with increased levels of obesity, diabetes, weight gain and other non-communicable diseases.[2].[3]

More than 4 billion people could be overweight or obese by 2035, compared with 2.6 billion in 2020 according to a report published by the World Obesity Federation [4].

The statistics in the UK are equally alarming. Almost three quarters of people aged 45-74 in England are overweight or obese according to The Health Survey for England 2021 published late last year. Overall numbers show that 68.6% of men and 59% of women are either overweight or obese [5].

In Scotland, figures from 2021 put 31% of adults in the obese category and 36% in the overweight category, while in Wales in the same year 26% of women and 23% of men reported being obese [6].

Our children are inheriting the poor eating patterns that have become so pervasive in adults who are lured in by clever marketing to consume processed convenience food that are calorific and void of nutrients. This has contributed to 23.4% of 10-11-year-olds in England being obese and 14.3% being overweight according to data from the National Child Measurement Programme published by NHS Digital [7].

The problem is exacerbated in the most deprived areas of England where prevalence of obesity or being overweight is 9 percentage points higher than in the least deprived areas of the country. Moreover, people from black ethnic groups have been shown to have the highest rates of excess weight with 72% of adults from these groups classified as overweight or living with obesity in the year ending November 2021 – the highest percentage out of all ethnic groups [8].

In lower income countries and communities, a preference towards highly processed foods is a major factor in increasing rates of obesity [9]. Figures estimate that access to healthy food is unaffordable for almost 3.1 billion people worldwide. Our agrifood systems have evolved today so that the cost of a healthy diet is five times greater than the cost of diets that meet our energy requirements only through a staple cereal. Low-priced foods high in energy and low in nutritional value are on the rise. And this trend has led to an increase in associated health risks linked to mortality and diseases such as diabetes, obesity and overweight. Statistics indicate that between 702 and 828 million people were affected by hunger in 2021. On the other hand, numbers in 2022 show that more than one billion people are obese and by 2025, around 167 million people – adults and children – will become less healthy because they are overweight or obese [10][11].

The world’s food systems are out of kilter and imbalanced. They have not been designed to meet our dietary needs, but instead focus on business gains. As the cost-of-living crisis rages on and many struggle to make ends meet, food choices depend largely if not solely on affordability. The cycle becomes a vicious one as eating low-cost often means consuming calorific, processed foods packed with additives and lacking in vitamins and minerals. Inevitably then, those who are already financially burdened, are saddled with the health consequences of consuming products that companies know very well lead to overweight and obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and gastrointestinal disorders [12][13].

Understanding the processing spectrum

As supermarkets lure us in with clever marketing strategies, brightly coloured packaging and dubious health claims, it has become more important than ever for us to understand our food and how it is processed.

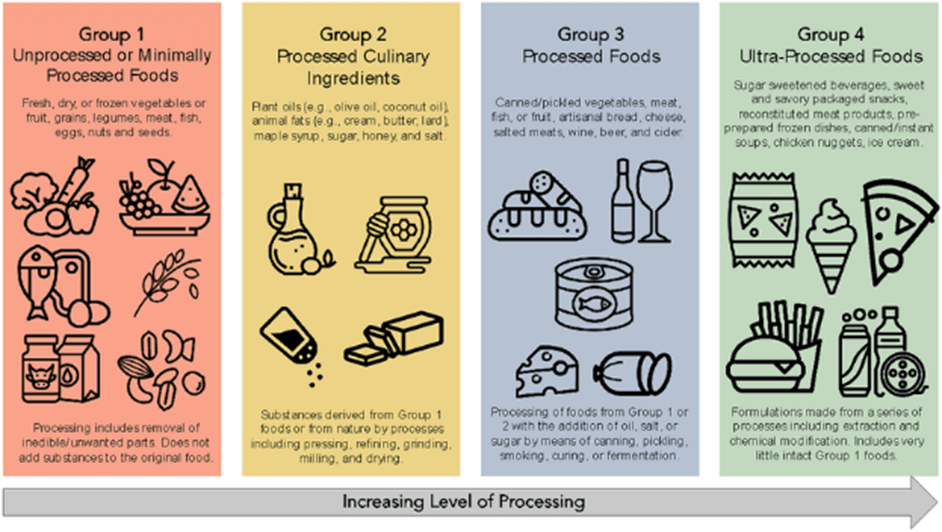

The NOVA international classification system, developed by Carlos Monteiro and his team at the Center for Epidemiological Research in Nutrition and Health at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, provides a useful starting point to understand different levels of food processing [14].

In reality, processed foods are designed to increase flavour, extend shelf-life, and ensure transportability, all of which reduce nutritional quality [15].

It is vital to recognise that there are varying levels of food processing. Because most of us no longer live in agrarian settings, most of our food tends to be processed to some degree.

Unprocessed foods or those that are minimally processed are those that may have been roasted, boiled, ground, dried, crushed, fermented or made easier to eat for example by removing inedible or unwanted parts. For example, spiralized courgettes or “courgetti”, frozen blueberries, walnuts (with their shells removed), and salmon which has been descaled and filleted. Generally speaking, these processes do not rely on the addition of salt, sugar, fats, additives, etc., and instead focus on making the food more convenient to use, long-lasting and/or diverse.

You then have processed culinary ingredients such as butter, sugar, salt, condiments and oils that may be dried, pressed, ground, milled and refined to season and cook foods in the unprocessed fresh food category to enhance flavour. These ingredients – think paprika, olive oil, cream, and maple syrup – are not meant to be eaten on their own.

Processed foods such as tinned sardines, canned chickpeas, baked beans, camembert and focaccia, for example, often combine oil, salt, sugar or the substances from the second group of culinary ingredients, with foods from the unprocessed or minimally processed group. These foods may be cooked, baked, preserved or fermented without alcohol to increase their durability or enhance their appearance, smell and taste.

Ultra-processed foods, by contrast, are modified to such an extent through multiple types of processing that they barely resemble the fresh or minimally processed items in the first group. These foods and drinks such as chicken nuggets, ice-cream, instant noodles, vegetarian burgers, cheese twists, tortilla wraps, bourbon biscuits, breakfast cereals, margarine, instant soups, sausage rolls, cakes, ready meals and soft drinks, often include salt, sugar, oils and fats, as well as other ingredients and additives like lactose, emulsifiers, gluten, hydrolysed proteins, high-fructose corn syrup, and artificial colours and flavourings. These ingredients have undergone significant processing themselves. Many of these additives are found only in ultra-processed foods in order to mask unpleasant tastes or enhance the appearance, attractiveness and flavour of the final product.

—————————————————————————————————————–

Image credit: Spectrum of processing of foods based on the NOVA classification. The figure provides examples of foods and types of processing methods within each NOVA classification group. Definitions are adapted from Monteiro et al. (2018) [8]

————————————————————————————————————

Because many ultra-processed foods contain so little real food, one can understand why they lack any nutrient density. But the problem doesn’t stop there. Not only are these foods lacking in vitamins, minerals, healthy protein, fibre and more, their high levels of salt, sugar, oils, fats and additives makes them addictive – so we end up consuming more empty calories because these foods don’t satiate us like whole foods do.

What are the consequences of a diet dominated by ultra-processed foods? Studies have shown associations between such foods and obesity, weight gain, cardio-metabolic risks, cancer, type-2 diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome and depression. Among kids, the effects include obesity, weight gain, cardio-metabolic risks and asthma [16][17][18][19][20][21][22] .

Food labels: The devil is in the detail

So what can we do to avoid the processed food trap?

Reading food labels carefully may be one way to reduce our reliance on foods filled with artificial flavourings, colours and ingredients.

Food labelling is strictly governed by law in the UK and so false, misleading descriptions are illegal. Manufacturers can only make statements about their foods if they are accurate. For example, companies cannot label a product “reduced calorie” unless it is much lower in calories than the regular version.

Manufacturers are mandated to show the country of origin if customers might be misled without this information, for example, if the label for a packet of paneer shows the Taj Mahal, but the paneer is made in the UK.

If the primary ingredient in the food comes from a place that is different to where the product says it was made, the label must show this. For example, a pork pie labelled ‘British’ that is produced in the UK with pork from Germany, must state “with pork from Germany” or “made with pork from outside the UK” [23].

Foods must indicate if they have undergone any processing, for example, “smoked” salmon, “dried” cherries, or “shredded, pickled” beetroot.

Every ingredient must be listed on labels for foods which contain two or more ingredients. Ingredients must be listed in order of weight, with the main ingredient first. Companies are also expected to show the percentage of an ingredient if it is highlighted by the labelling or a picture on a package, for example “extra cheese”, mentioned in a “cheese and onion pasty”, or a food normally connected with its name by consumers, for example, fruit in a summer pudding.

Images on food packaging must also be accurate. So, a pot of blueberry yoghurt which contains artificial flavouring rather than real fruit, is not permitted to have a picture of blueberries on the pot (although manufacturers have gotten away with cartoon blueberries before).

Food packaging must show an appropriate warning on the label if the food contains certain ingredients. For example, if the food contains artificial colours such as “allura red (E129)”, “carmoisine (E122)”, or “quinoline yellow (E104)”, the label should state “may have an adverse effect on activity and attention in children”.

Exploiting legal loopholes & The bitter truth about sugar

Food labels are intended to protect and inform consumers, but many can be misleading. Sadly, our quest to select foods with more vitamins, minerals and fibre, and less trans-fat, cholesterol, and salt, is not always a straightforward one. Navigating food labels can be a minefield.

Food labels are intended to protect and inform consumers, but many can be misleading. Sadly, our quest to select foods with more vitamins, minerals and fibre, and less trans-fat, cholesterol, and salt, is not always a straightforward one. Navigating food labels can be a minefield.

Assessing healthiness based on labels can be tricky. Positive labels such as “natural”, “organic”, and “low-fat” can be deceiving in terms of the benefits they confer. Some data, such as the content of “free sugars”, i.e. the sugar that is added to a product rather than the sugar that appears naturally in a piece of fruit, for example, is not legally required to appear on a label.

Instead, products must show “total sugars” which include both naturally occurring sugars and added sugars. This makes it difficult for consumers to know how much added sugar they are consuming. For example, full-fat fresh milk contains 9.4g of total sugars per serving (200ml), but none of these are “free sugars” as they all come naturally from the milk. In comparison, a brand of chocolate milk shows the same number of total sugars – 9.4g per 200ml – but upon closer inspection of the ingredients, this includes a sweetener, sucralose, and rice starch which breaks down into sugar [24].

Appreciating how sugars and starches are highlighted on food labels is vital if we are to make healthier choices.

For example, despite having a very high glycaemic index (GI), refined starches such as maltodextrin [25], which can be found in many processed foods such as pasta, cereals, salad dressings and sweets, do not have to be labelled as sugars. In fact, maltodextrin is excluded in the definition of sugar used for nutrition labelling [26]. High GI foods are rapidly absorbed into our bloodstream and lead to sugar spikes, and excess sugar is often a major culprit for obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Fructose is another problematic ingredient. It occurs naturally in fruit and honey but is also used as a free sugar in confectionery and sugary drinks. Food manufacturers can include a health claim on their products stating that the consumption of foods containing fructose leads to a lower blood glucose rise compared to foods containing sucrose or glucose. This is if the fructose used reduces the content of sucrose or glucose by 30%.

But despite the truth that fructose has a lower GI than sucrose and glucose, consuming high amounts can affect our liver and compromise the function of our hunger and satiety hormones, leptin and ghrelin, so we think we are still hungry and end up overeating. Unlike glucose, which can be metabolised by all of our cells, fructose can only be broken down by our liver. High fructose consumption has been associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, insulin resistance and diabetes, and obesity. So the suggestion that fructose is a healthy sugar alternative is too simplistic and misleading [27][28][29][30]. The fact is, fructose is taxed like other sugars, so why are companies allowed to attach a positive health claim to it being a good substitute for sucrose?

All carbohydrate foods including grains, fruits, cereals, dairy and starchy vegetables contain sugars. In the case of whole foods, some of these sugars are bound to other nutrients, such as fibre, fat and protein, which help slow their release into the bloodstream and thus reduce the sugar highs and subsequent dramatic crashes that we experience. Avoiding “free sugars” – the ones added to products like fizzy drinks, sweets, yoghurts, sauces and breakfast cereals, we can maintain balanced energy levels and a healthy weight.

Since 2018, the UK has taxed drinks which contain 5g or more free sugar per 100ml. The levy saw a fall of 35.4% in total sugar sold in soft drinks between 2015 and 2019 [31]. However, despite this, obesity levels have continued to rise, suggesting that the government needs to enact tougher policies to push food companies towards healthier and more sustainable manufacturing practices.

The way forward: How to make healthier choices.

The way forward: How to make healthier choices.

In March, the British Association of Nutritional and Lifestyle Medicine, supported the resignation of Henry Dimbleby from his role as government food adviser in protest at the government’s inaction against obesity and junk food culture. BANT has continuously advocated for stronger policies to tackle the obesity epidemic.

Prior to stepping down from his role, Dimbleby published the National Food Strategy, an independent review for government aimed at reshaping our food system so that it is stable, safe, sustainable, affordable and nutritious. Dimbleby’s recommendations include the following:

- Introduce a sugar and salt reformulation tax and use some of the revenue to help get fresh fruit and vegetables to low-income families

- Introduce mandatory reporting for large food companies

- Invest £1 billion in innovation to create a better food system

- Strengthen government procurement rules to ensure that taxpayer money is spent on healthy and sustainable food.

Without adequate government support and the influence of powerful food manufacturers whose profit lines are prioritised ahead of consumer wellbeing, navigating a healthy diet and knowing what to eat has become more challenging than ever before.

The food and drink industry is the UK’s largest manufacturing sector, surpassing economic contributions from the automotive and aerospace manufacturing industries. In 2022, total business investment in the industry amounted to £4 billion, up by 7.9% from 2020 [32]. With such power, BIG Food has the potential to transform consumer health, reduce chronic disease and sustain a more productive population. Conscientious, science-backed policies are the need of the hour.

But there is a lack of political will to bring about meaningful change. The government has failed to do its part to tackle obesity and associated chronic conditions by delaying restrictions on junk food promotions and advertising to children, and refusing to tax manufacturers on the sugar they add in processed food [33].

So, what can we do?

Thankfully, there are several shopping strategies we can adopt to rid ourselves of the ultra-processed food trap.

Thankfully, there are several shopping strategies we can adopt to rid ourselves of the ultra-processed food trap.

Better awareness of food labels is crucial starting point to identify and reduce the amount of processed and ultra-processed food we consume.

One indicator of a processed product will be its never-ending list of ingredients, many of which seem unrecognisable or impossible to find in natural form. In most cases, less is more. Take butter, for example. The sole ingredient in one brand of organic butter is cow’s milk. Compare this with a brand of margarine, which has the following: water, vegetable oils in varying proportions (palm oil, rapeseed oil), reconstituted buttermilk, salt, emulsifier: mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids; preservative: potassium sorbate; acidity regulator: lactic acid; vitamin E, flavouring, colour: carotenes; vitamin A and vitamin D. Which would you pick?

Keep an eye out for additives and avoid foods with these ingredients as much as possible. Additives include artificial colours and dyes, artificial flavours and flavour enhancers and non-sugar sweeteners. It’s also worth taking stock of processing terms. So foods and drinks which indicate that they have been “carbonated”, or include “bulking”, “anti-caking”, and “glazing” agents, for example, should be avoided.

When shopping, stay away from products which include “free sugars” such as fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, fruit juice concentrate, cane sugar, crystalline sucrose, glucose and honey. Honey is often perceived as a healthier sugar, because of its potential anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial properties. But it is also high in fructose and is absorbed in the same way as other sugars, so it is important to consume in moderation [34].

Steer clear of buy-one-get-one-free deals, which are often applied to junk foods. These deals persuade us to buy more than we need, resulting in excessive calories or resulting in food waste when these foods cannot be finished.

The traffic light system gives us some indication of which foods may be healthy, but it has its limitations. Look deeper at the list of ingredients and you’ll see the traffic light only reveals so much about food composition and nutrient density. So don’t rely solely on the green light when choosing what to put in your basket.

Let’s look at tortilla wraps. They contain only 1.5g of sugar per wrap, and so they get a green light in this category (while fat, saturated fat and salt all come under the amber light). Does that mean tortillas are a fairly nutritious choice? Let’s scan the ingredients: fortified British wheat flour (wheat flour, calcium carbonate, niacin, iron, thiamin), water, palm oil, humectant: glycerol; raising agents: disodium diphosphate, sodium hydrogen carbonate; sugar, acidity regulator: citric acid; emulsifier: mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids; preservative: calcium propionate; salt, wheat starch, flour treatment agent: l-cysteine. Does that seem healthy? Should our daily bread require so many ingredients?

How about batch cooking and freezing our own tortillas for easy access? This recipe for homemade flour tortillas uses flour, baking powder, salt, olive oil and water. Don’t those real food ingredients seem so simple and appealing?

How about batch cooking and freezing our own tortillas for easy access? This recipe for homemade flour tortillas uses flour, baking powder, salt, olive oil and water. Don’t those real food ingredients seem so simple and appealing?

Be savvy about marketing traps. The word “natural”, for instance, evokes a sense of healthy, unprocessed food. The Food Standards Agency states that “natural” should mean that the food is made up of ingredients produced by nature. But many foods contain chemicals renamed to be more appealing to consumers. “Carrot concentrate”, for example, is a highly processed ingredient that is used to give foods a bright yellow hue [35].

Organic food is certainly better for you from the point of view that it is free from harmful pesticides. However, just because something is certified organic does not mean it is nutritious, as this simply indicates how the food is produced. Organic foods can be high in saturated fat and sugar.

Similarly, “plant-based” is often synonymous with healthiness (and climate consciousness), however, many plant-based items such as meat substitutes, can be highly processed, high in fat, salt and sugar [36][37].

Foods that claim to be “low sugar” can still be calorific as well as high in fat. The label “no added sugar” can be misleading too, as manufacturers can use fruit juice concentrate as a sweetener which does not have to be labelled as “added sugar”.

“Low fat” foods indicate that a food has less than 3g of fat per 100g. However, it is common for food producers to substitute the eliminated fat with sugar to maintain flavour.

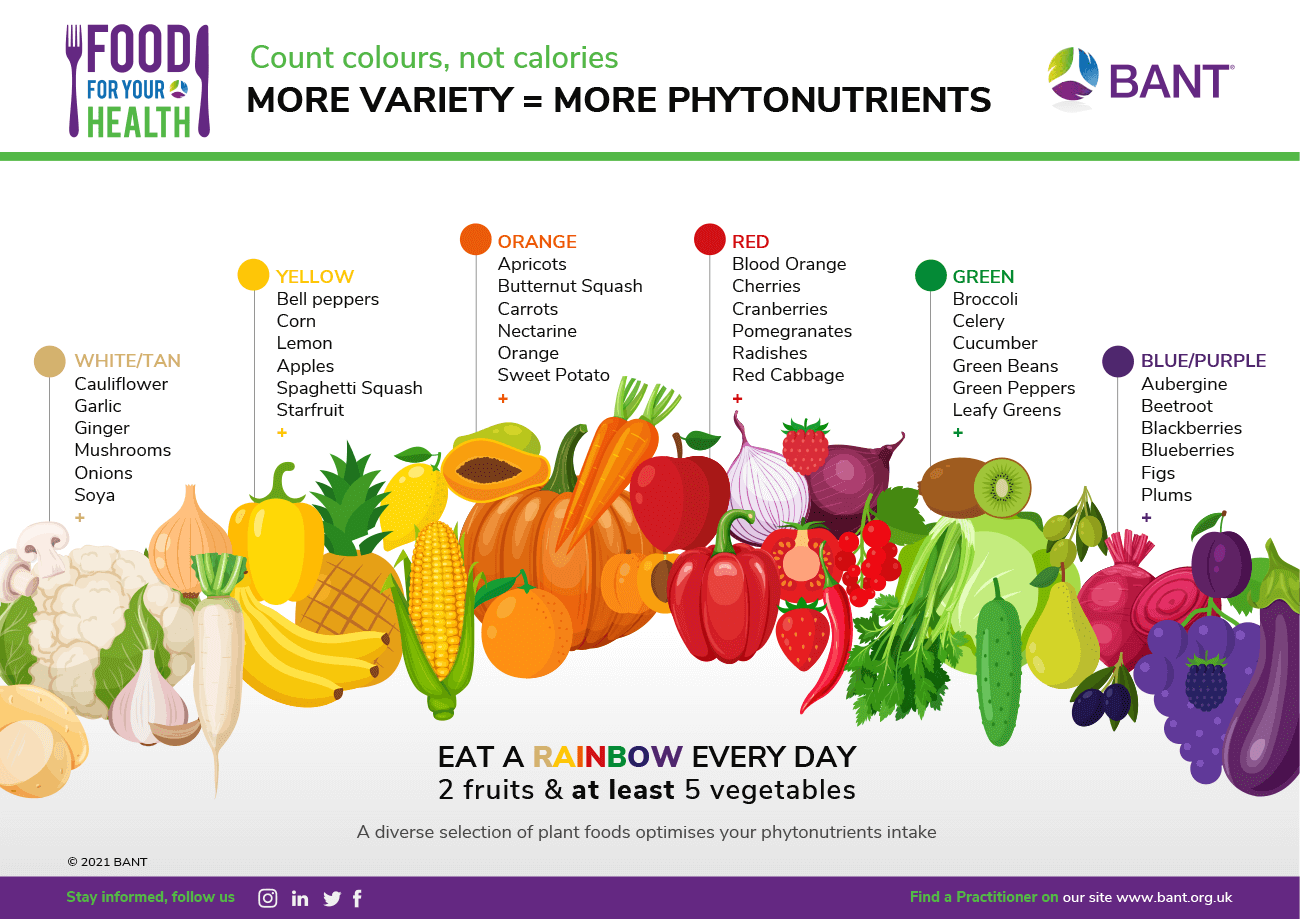

One of the best things we can do for ourselves is return to a culture of whole foods and home-cooking. Instead of perusing the endless aisles of packaged food in your supermarket, spend some time in the fresh fruit, veg, meat and fish sections. We lead busy lives, so sometimes relying on some minimally processed foods like a stir fry mix with beansprouts peppers, sweetcorn, cabbage, carrot and onions is our best bet.

Read those labels and keep things simple. Look out for seasonal produce to bring colour and variety to your table while saving costs. Think brussel sprouts in the winter, rhubarb in early spring, wild nettles in the summer and pumpkins in autumn.

Fill your basket with colour and meal plan so you get the most out of your fresh produce. A tray of roasted vegetables works beautifully with a piece of roasted chicken and leftovers can be eaten for lunch the next day. Build hearty stews or daals with vegetables, lentils, herbs and spices. Create deliciously cool salads with crisp apples, walnuts and pomegranates. Take inspiration from different cuisines and play around with ingredients to maximise vitamin and mineral diversity.

Author:

Vandana Chatlani, BANT Registered Nutritionist ® NT Dip, mBANT, rCNHC

NOTES TO EDITORS:

BANT is the leading professional body for Registered Nutritional Therapy Practitioners in one-to-one clinical practice and a self-regulator for BANT Registered Nutritionists®. BANT members combine a network approach to complex systems, incorporating the latest science from genetic, epigenetic, diet and nutrition research to inform individualised recommendations. BANT oversees the activities, training and Continuing Professional Development (CPD) of its members.

Registered Nutritional Therapists are regulated by the Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council (CNHC) that holds an Accredited Voluntary Register (AVR) for the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA). A report by the Royal Society for Public Health and the Professional Standards Agency made a key recommendation that AVR practitioners have the authority to make direct NHS referrals, in appropriate cases, to ease the administrative burden on GP surgeries. BANT nutrition practitioners are the key workforce asset to harness 21st century lifestyle medicine to tackle the rising tide of stress-related fatigue, obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, dementia and other chronic diseases.

To find a BANT nutrition practitioner, please click here

BANT WELLBEING GUIDELINES:

The BANT Wellbeing Guidelines are specifically designed to provide clear, easy to understand general information for healthy diet and lifestyle when personalised advice is not available.

BANT launched it’s 2021 Food for your Health campaign to tackle diet-induced obesity and metabolic dysregulation and combat the junk food culture by promoting healthy food and lifestyle choices. We offer a range of free, open-access resources, and have a network of over 3,500 Nutrition Practitioners throughout the UK.

References:

[1] Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases-Related Dietary Nutrient Profile in the UK (2008–2014), https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/5/587

[2] Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3378592/#pmed.1001242-DeSchutter

[3] Manufacturing Epidemics: The Role of Global Producers in Increased Consumption of Unhealthy Commodities Including Processed Foods, Alcohol, and Tobacco, https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001235

[4] World Obesity Atlas 2023, https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/wof-files/World_Obesity_Atlas_2023_Report.pdf

[5] Health Survey for England, 2021, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2021/health-survey-for-england-2021-data-tables

[6] Obesity Statistics, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn03336/

[7] National Child Measurement Programme, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-child-measurement-programme

[8] Overweight Adults, https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/health/diet-and-exercise/overweight-adults/latest

[9] World Obesity Atlas 2023, https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/wof-files/World_Obesity_Atlas_2023_Report.pdf

[10] World Obesity Day 2022 – Accelerating action to stop obesity, https://www.who.int/news/item/04-03-2022-world-obesity-day-2022-accelerating-action-to-stop-obesity

[11] The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022, https://www.fao.org/3/cc0639en/online/sofi-2022/introduction.html

[12] Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3378592/#pmed.1001242-DeSchutter

[13] Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/ultraprocessed-foods-what-they-are-and-how-to-identify-them/

[14] The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/un-decade-of-nutrition-the-nova-food-classification-and-the-trouble-with-ultraprocessing/2A9776922A28F8F757BDA32C3266AC2A

[15] Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3378592/#pmed.1001242-DeSchutter

[16] Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Narrative Review, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7399967/

[17] Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7844609/

[18] Ultra-processed Foods and Cardiovascular Diseases: Potential Mechanisms of Action, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8483964/

[19] Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of obesity: a prospective cohort study of UK Biobank, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8137628/

[20] Ultra-Processed Foods Are Not “Real Food” but Really Affect Your Health, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6723973/

[21] Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a systematic review of epidemiological studies, https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12937-020-00604-1 /

[22] Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Among Participants of the NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2757497

[23] Food labelling and packaging https://www.gov.uk/food-labelling-and-packaging/food-labelling-what-you-must-show

[24] Looking at labels https://www.nutrition.org.uk/putting-it-into-practice/food-labelling/looking-at-labels/)

[25] Nutrition, Health, and Regulatory Aspects of Digestible Maltodextrins, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4940893/

[26] A definition of free sugars for the UK, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5962881/

[27] UK nutrition and health claims register, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/867379/UK

[28] The negative and detrimental effects of high fructose on the liver, with special reference to metabolic disorders, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6549781/

[29] Fructose and Sugar: A Major Mediator of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5893377/

[30] Effects of High-Fructose Diets on Central Appetite Signaling and Cognitive Function, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4429636/

[31] Sugar tax, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/explainer/sugar-tax

[32] Key facts and stats, https://www.fdf.org.uk/fdf/business-insights-and-economics/facts-and-stats/

[33] Britain’s diet is more deadly than covid, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/britains-diet-is-more-deadly-than-covid-jc33p0krj

[34] Honey and Health: A Review of Recent Clinical Research, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5424551/

[35] Are you being fooled by food labels? https://www.bbc.co.uk/food/articles/are_we_fooled_by_food_labels

[36] Plant-Based Alternative Products: Are They Healthy Alternatives? Micro- and Macronutrients and Nutritional Scoring, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8838485/

[37] Foods for Plant-Based Diets: Challenges and Innovations, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7912826/