10 Mar 2023 Why is everyone talking about Dementia?

Why is everyone talking about Dementia?

Dementia is a public health priority with a huge human and economic burden. 50 million people are living with dementia globally and 850,000 of those are in the UK (1). As the population grows it is predicted that by 2025 over one million people in the UK may have dementia and by 2050, 152 million people in the world will be living with dementia (1). Despite millions of pounds of investment in research, there is currently no cure for the disease. There is now a rising focus on preventative strategies due to the scarcity of neuroprotective treatments and the increased incidence of the disease globally. In this article we will dig deep into the risk factors for this devastating condition and discuss why adopting healthy lifestyle choices at a young age can reduce the risk of dementia in later life.

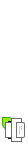

What is Dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term for several types of neurological conditions affecting the brain. The most common include Alzheimer’s Disease, Vascular Dementia, Frontotemporal Dementia, Lewy Body and Mixed Dementia. These conditions affect different parts of the brain and therefore will affect individuals differently. Dementia is a progressive disease usually developing over several years which causes significant disability and dependency to individuals in their everyday life’s. It can affect how we remember things like people’s names and even everyday words, how we organise ourselves and carry out everyday tasks, how we communicate, how we orientate to our surroundings, how we behave, how we comprehend information and how we judge things. People living with dementia start to appear different to their family and friends and as the disease progresses, they will most likely require help with practical tasks including washing, dressing, toileting, cooking, eating, and drinking. To help understand further we will now discuss different types of dementia and their impact on individuals.

Dementia is an umbrella term for several types of neurological conditions affecting the brain. The most common include Alzheimer’s Disease, Vascular Dementia, Frontotemporal Dementia, Lewy Body and Mixed Dementia. These conditions affect different parts of the brain and therefore will affect individuals differently. Dementia is a progressive disease usually developing over several years which causes significant disability and dependency to individuals in their everyday life’s. It can affect how we remember things like people’s names and even everyday words, how we organise ourselves and carry out everyday tasks, how we communicate, how we orientate to our surroundings, how we behave, how we comprehend information and how we judge things. People living with dementia start to appear different to their family and friends and as the disease progresses, they will most likely require help with practical tasks including washing, dressing, toileting, cooking, eating, and drinking. To help understand further we will now discuss different types of dementia and their impact on individuals.

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia largely affecting individuals over 65 years (2). Currently, 520,000 in the UK are living with AD (1). It is a progressive condition where symptoms steadily become worse over time. Two proteins throughout the brain called amyloid beta and tau tangles cause neuronal damage and interrupt the signalling pathways in the brain. This causes loss of brain connections, loss of function and widespread brain damage. Initially individuals often experience memory difficulties but as the disease progresses further complications develop including disorientation, language decline, reduced problem solving, personality changes, swallowing difficulties and changes in mood. In time many individuals will be unable to care for themselves and require care from family or social support.

Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia affecting over 150,000 in the UK (3). It is caused by a disruption in the supply of blood to the brain causing a reduction in the supply of oxygen most commonly due to strokes or transient ischaemic attacks. It is prevalent among the elderly population and causes individuals to experience cognitive difficulties, depression and anxiety and reduced problem-solving skills (3).

Frontotemporal dementia affects the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain and mainly impacts individuals between the ages of 45 to 65 years. The frontal lobe controls high level cognitive skills including our emotions, personality and behaviour, problem solving, memory, language, and judgement. These skills can be impaired in frontotemporal dementia (4).

Dementia with Lewy bodies is a progressive condition which often affects an individual’s movement and motor skills and may also cause hallucinations (5). Unlike other types of dementia, memory is not as affected with Lewy body dementia.

Mixed dementia occurs when an individual is considered to have more than one type of dementia and is more common in older adults.

What happens to our brains as we age?

As we age our brains can become less efficient, brain signals are lost, brains can become smaller, thought processes slow down and our memory isn’t as sharp as it once was. This is ageing, a normal part of getting older and shouldn’t be confused with dementia. It is important to point out that cognitive decline does not always lead to dementia. Dementia is not a normal part of ageing and not everyone will get dementia. Although dementia can affect some young people, age is the biggest risk factor for the condition and mostly affects people over the age of 65. By 2040, it has been predicted that almost 1 in 4 people in the UK will be aged over 65 years (1). We will now consider other risk factors for dementia.

Another unmodifiable risk factor for dementia is gender. In the UK, 62% of people living with dementia are women, worryingly it is the biggest cause of death in women within the UK (1). This is not only related to women living longer than men but unsurprisingly to the lack of educational opportunities historically for women. Oestrogen is a female sex hormone which has protective properties for the brain but as the levels of this hormone decline following the menopause, women are placed at an increased risk of dementia (6).

Ethnicity also plays a role in dementia prevalence. Within the black and South Asian population, 50,000 people are predicted to be living with dementia by 2026 and by 2051, this number is forecast to rise to 172,000 (1). This is related to these individuals being at an increased risk of heart disease, diabetes and hypertension which are all risk factors for dementia (1).

Genetics only accounts for a small proportion of people living with dementia. Just because we have a relative living with dementia does not necessarily mean that we will inherit the condition. Genes is only one feature in a long list of factors that may contribute to an increased risk of dementia (7).

Why is it important to maintain a healthy lifestyle from a younger age?

It is important to point out that it is usually not until an individual presents with cognitive difficulties that dementia is recognised. At this point, a cascade of damage to the brain has already occurred without experiencing any symptoms. Therefore, making healthy lifestyle choices at an early age can make an enormous difference to dementia developing later in life. For individuals with a diagnose of dementia, lifestyle factors can also slow down the progression of the disease. As several risk factors for dementia are interrelated, by modifying one can positively reduce another.

A growing body of evidence recognises several modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia. The Lancet commission report has identified that modifiable risk factors may reduce the risk of dementia by 40% (8). Let’s now look at these risk factors in more detail.

Blood Pressure

Maintaining a healthy blood pressure in mid-life will reduce the incidence of vascular dementia in later life.

Smoking

Studies show that smokers are at an increased risk of dementia compared to non-smokers (8). Smoking is a risk factor for several other non-communicable disease including heart disease, stroke diabetes and cancer and individuals who smoke are at an increased risk of early death (8). Toxins present in tobacco contribute to inflammation, a key feature of AD.

Alcohol

Excessive alcohol consumption contributes to an increased risk of disrupted communication pathways in the brain, cognitive decline, and dementia (8).

Blood Sugar

Regulating blood sugar control is an important risk factor for dementia. Diabetes increases the risk of heart disease and stroke which affects blood vessels transporting oxygen and nutrients to the brain. Cognitive decline can develop when blood vessels become damaged in the brain. Raised blood sugar levels causes inflammation, a key feature of AD (9).

Cognitive Stimulation

Accessing educational opportunities at a younger age and lifelong educational attainment significantly contributes to cognitive health and decreases the incidence of dementia in later life (8). However, new research has shown that higher educational attainment, mental stimulation, and social engagement in adulthood may outweigh disadvantaged childhood education (10). Keeping both mentally and socially active by participating in cognitively thought-provoking activities contribute to building cognitive reserve in the brain. Individuals with more cognitive reserve have been shown to be more resilient against cognitive decline and dementia (11).

Sleep

Sleep is a time for healing and a time for the body to repair. Disturbed sleep has been associated with an increase in inflammation which may then lead to AD (8).

Studies have also highlighted depression, anaemia, air pollution, traumatic brain injury and hearing impairment as modifiable risk factors for dementia (8). Let’s move on to look more closely at diet and its link to dementia.

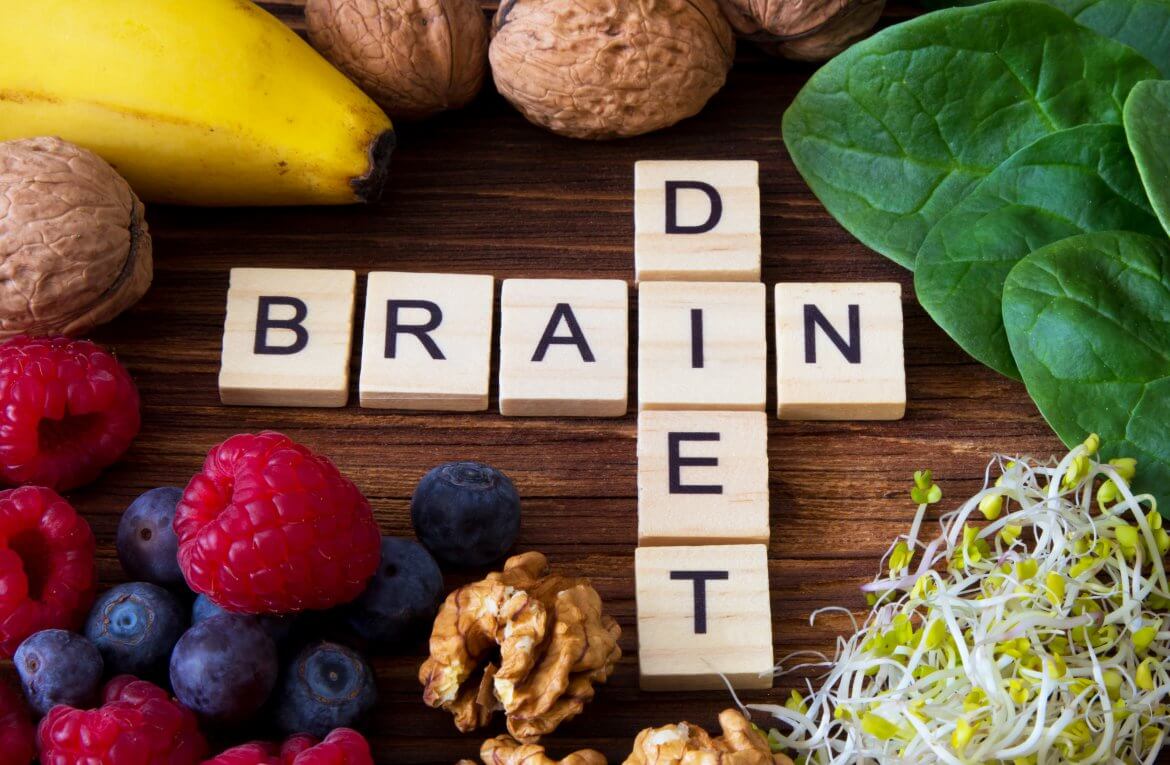

Feed your brain

Diet plays a key role in preventative medicine, but individual dietary choices can be influenced by several factors. These include individual preferences, age, gender, culture, religion, education, income, health conditions, motivation, values and dietary knowledge and cooking skills (12). Through a personalised nutrition approach these individualities can be identified. Like many other health conditions including heart disease, stroke, obesity, cancer and diabetes, the food we choose to eat can contribute towards disease progression or disease prevention. Studies have shown that individuals with these conditions are more likely to develop cognitive decline. Recently research has focused more on dietary patterns that look at combining food and nutrients to provide a synergistic effect rather than individual nutrients in isolation (13).

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet has become a cornerstone in several non-communicable diseases and neurodegenerative conditions. Rather than looking at individual nutrients, it emphasises a diverse high nutritional quality balanced diet with a key focus on plant origin food, rich in natural ingredients and high in vitamins, minerals, and dietary fibre. It offers protective anti-inflammatory properties, an abundance of antioxidants to combat free radicals and oxidative stress which can cause harm in the body, offers satiety, and contributes to an improvement in the metabolism of glucose and lipids. Key ingredients of the diet include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans, nuts, seeds, healthy unsaturated fats including olive oil, increased consumption of fish and shellfish, red wine in moderation and lower amounts of dairy products and red meat (14).

DASH Diet

Another diet offering a multi-nutrient effect and improvements in cognition and memory is the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet (DASH). As well as protecting the brain, the DASH diet has also been shown to protect the heart and offer better blood pressure control (13). Like the Mediterranean diet, it builds nutrient dense meals around the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fat free or low-fat dairy, fish, poultry, beans, nuts, seeds, and vegetable oils. It places a limit on consuming salt, fatty meats, full fat dairy, sweets, and sugar sweetened drinks.

Mind Diet

A combination of both the Mediterranean and the DASH diet called the MIND diet has been highlighted as containing neuroprotective nutrients. This is in comparison to the western diet which is high in processed food, low in fruits and vegetables, high in saturated and trans fats, salt, excess sugar and low in fibre. The western diet has played a huge contribution to the rising rates of obesity and in the UK 1 in every 4 adults are classified as obese (15). High BMI is linked to several non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, some cancers, and musculoskeletal disorders (16). Obesity in mid-life has been found to contribute to the development of dementia later in life (17).

The Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiome refers to the collection of microorganisms present within the gut including bacteria, viruses and fungi. They play numerous functional roles in the body including food digestion and immunity to protect against pathogens (18). The “gut-brain axis” refers to the two-way communication network between the brain and the bacteria present in the gut. Having a nutritious diet plays an important role in supporting the production of beneficial bacteria. Studies have highlighted lack of diversity of the gut microbiome is a risk factor for neurodegeneration and disrupts the communication pathway between the gut and the brain (18).

Keep yourself active through a personalised approach

Being physically active is considered one of the most important preventative measures for maintaining cognitive ability and preventing dementia (19). Being physically active from a young age can positively benefit brain health later in life (20). Exercise releases chemicals in the brain called endorphins, boosts self-esteem, improves sleep quality, promotes relaxation, and enhances mood (21) and energy levels, decreases blood pressure and cholesterol levels. Being physically active in older age can positively preserve cognition in comparison to being sedentary (22). Exercise increases the production of signalling cells, reduces inflammation and oxidative stress, and increases blood flow within the brain improving memory, thinking and judgement skills and slows cognitive decline (22). In addition, being physically active increases the circulation of blood throughout the body, reduces the risk of falls, strengthens bones and muscles, helps to manage your weight, reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, heart disease, some cancers, stroke, falls, depression, and dementia (21). Government guidelines advocate 150 mins of being physically active throughout the week, this can be broken down to 20-30 mins daily (23). Dementia prevention is not linked to one exercise, or one activity (20) and exercise interventions require a personalised approach considering an individual’s health condition and what type of exercise they enjoy taking part in. Studies have shown that regular engagement in a sport or exercise training has been shown to have the greatest benefit in reducing the incidence of dementia (19). For some individuals being physically active may be through household activities such as climbing stairs, cleaning, and gardening (19).

Make that first step now and keep your brain healthy

Now is the time to implement change. Through a personalised nutrition approach, modifiable risk factors for dementia can be identified at an early age to decrease the incidence of dementia in later life. Personalised nutrition looks at the whole person throughout their life using a systems biology approach. This helps to understand how everything in our body is interconnected and explores how diet implements health and prevents disease. As part of an integrative healthcare team Nutritional Therapy Practitioners play a pivotal role in preventative healthcare. Using an evidence-based approach they work alongside conventional medicine professionals to tackle the root causes of disease and address nutritional imbalances, educating and empowering individuals to make healthy choices and supporting them through the process.

Author: Hayley Cowie, Nutritional Therapy BSc Student CNELM & ex NHS Stroke & Dementia Nurse

Hayley is currently studying for a BSc Honours in Nutritional Science at the Centre for Nutrition Education and Lifestyle Management (CNELM).

Hayley is currently studying for a BSc Honours in Nutritional Science at the Centre for Nutrition Education and Lifestyle Management (CNELM).

Hayley previously worked for the NHS for over twenty years in an acute teaching hospital. Throughout this period, she spent a considerable amount of time specialising in stroke care. Hayley also completed the Dementia Champions Programme through the University of the West of Scotland which provided her with knowledge and skills to support people living with dementia while in the hospital.

Continuing her passion for dementia, Hayley has written and developed learning tools on risk factors for dementia and cognitive stimulation for the British Association for Nutrition and Lifestyle Medicine (BANT). In her spare time, she loves to run, walk, read, and spend time with her family, friends, and two cocker spaniels Cooper and Obi.

References:

- UK Government., 2022. Dementia: applying All Our Health. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dementia-applying-all-our-health/dementia-applying-all-our-health [Accessed 18 October 2022].

- , 2021. Alzheimer’s Disease. [online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alzheimers-disease/ [Accessed 3 November 2022].

- , 2020. Vascular dementia. [online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vascular-dementia/ [Accessed 18 October 2020].

- , 2020. Frontotemporal dementia. [online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/frontotemporal-dementia/#:~:text=Frontotemporal%20dementia%20is%20an%20uncommon,the%20frontal%20and%20temporal%20lobes). [Accessed 18 October 2022].

- , 2019. Dementia with Lewy bodies. [online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dementia-with-lewy-bodies/ [Accessed 18 October 2022].

- Andrew, M.K. and Tierney, M.C., 2018. The puzzle of sex, gender and Alzheimer’s disease: Why are women more often affected than men? Women’s Health, 14, pp.1-8.

- Alzheimer’s Research UK., Genes and dementia. 2020. [online] Available at: https://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/dementia-information/genes-and-dementia/ [Accessed 18 October 2022].

- Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne, C., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C. and Costafreda, S.G., 2020. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 396, (10248), pp.413-446.

- Alzheimer’s Association., Diabetes and cognitive decline. [online] Available at: https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-dementia-diabetes-cognitive-decline-ts.pdf [Accessed 18 October 2022].

- Alzheimer’s Research UK., 2020. Differences in early-life education linked to dementia risk. [online] Available at: https://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/differences-in-early-life-education-linked-to-dementia-risk/ [Accessed 19 October 2022].

- Stern, Y., 2012. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology, 11(11), pp.1006-1012.

- Mozaffarian, D., Angell, S.Y., Lang, T. and Rivera, J.A., 2018. Role of government policy in nutrition—barriers to and opportunities for healthier eating. BMJ, 361, pp. 1-11.

- Dominguez, L.J., Veronese, N., Vernuccio, L., Catanese, G., Inzerillo, F., Salemi, G. and Barbagallo, M., 2021. Nutrition, physical activity, and other lifestyle factors in the prevention of cognitive decline and dementia. Nutrients, 13(11), pp.1-37.

- Ballarini, T., van Lent, D.M., Brunner, J., Schröder, A., Wolfsgruber, S., Altenstein, S., Brosseron, F., Buerger, K., Dechent, P., Dobisch, L. and Düzel, E., 2021. Mediterranean diet, Alzheimer disease biomarkers, and brain atrophy in old age. Neurology, 96(24), pp.2920-2932.

- , 2019. Obesity. [online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/obesity/ [Accessed 18 October 2022].

- World Health Organisation., 2021. Obesity and overweight. [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [Accessed 9 October 2022].

- Albanese, E., Launer, L.J., Egger, M., Prince, M.J., Giannakopoulos, P., Wolters, F.J. and Egan, K., 2017. Body mass index in midlife and dementia: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 589,649 men and women followed in longitudinal studies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, 8, pp.165-178.

- Borsom, E.M., Lee, K. and Cope, E.K., 2020. Do the bugs in your gut eat your memories? Relationship between gut microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Sciences, 10(11), pp.1-23.

- Zhu, J., Ge, F., Zeng, Y., Qu, Y., Chen, W., Yang, H., Yang, L., Fang, F. and Song, H., 2022. Physical and Mental Activity, Disease Susceptibility, and Risk of Dementia: A Prospective Cohort Study Based on UK Biobank. Neurology, 99(8), pp.799-813.

- Tait, J.L., Collyer, T.A., Gall, S.L., Magnussen, C.G., Venn, A.J., Dwyer, T., Fraser, B.J., Moran, C., Srikanth, V.K. and Callisaya, M.L., 2022. Longitudinal associations of childhood fitness and obesity profiles with midlife cognitive function: an Australian cohort study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 25 (8), pp.667-672.

- , 2021. Benefits of exercise. [online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/exercise-health-benefits/ [Accessed 9 October 2022].

- Wang, S., Liu, H.Y., Cheng, Y.C. and Su, C.H., 2021. Exercise Dosage in Reducing the Risk of Dementia Development: Mode, Duration, and Intensity—A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), pp.1-21.

- Department of Health and Social Care., 2019. UK Chief Medical Officers Physical Activity Guidelines. [online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf [Accessed 9 October 2022].

NOTES TO EDITORS:

BANT is the leading professional body for Registered Nutritional Therapy Practitioners in one-to-one clinical practice and a self-regulator for BANT Registered Nutritionists®. BANT members combine a network approach to complex systems, incorporating the latest science from genetic, epigenetic, diet and nutrition research to inform individualised recommendations. BANT oversees the activities, training and Continuing Professional Development (CPD) of its members.

Registered Nutritional Therapists are regulated by the Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council (CNHC) that holds an Accredited Voluntary Register (AVR) for the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA). A report by the Royal Society for Public Health and the Professional Standards Agency made a key recommendation that AVR practitioners have the authority to make direct NHS referrals, in appropriate cases, to ease the administrative burden on GP surgeries. BANT nutrition practitioners are the key workforce asset to harness 21st century lifestyle medicine to tackle the rising tide of stress-related fatigue, obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, dementia and other chronic diseases.

To find a BANT nutrition practitioner, please click here

BANT WELLBEING GUIDELINES:

The BANT Wellbeing Guidelines are specifically designed to provide clear, easy to understand general information for healthy diet and lifestyle when personalised advice is not available.

BANT launched its “Food for your Health” Campaign in February 2021 to provide open-access resources to help guide the public towards healthier food choices in prevention for diet-induced disease. Download a wide range of food and lifestyle guides, recipes, infographics, planning tools and fact sheets and start making healthy choices today.