20 Nov 2025 Understanding your liver: what it does, why it matters, and how to look after it

According to the British Liver Trust, mortality rates from liver disease have risen by more than 400% in the last 50 years, while rates of death from other major diseases, including heart disease, lung disease and cancer, have fallen[1]. The Trust also estimates that 1 in 5 people in the UK suffer from fatty liver disease[2], often categorised as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). This is a startling figure, and only one of several liver-related illnesses – such as alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), viral hepatitis and liver cancer – that affect the population.

The good news is that dietary and lifestyle changes, along with the conscious reduction of toxin exposure, can help us regain control and positively impact how our genes regulate metabolism, detoxification and overall liver function.

The liver is our body’s biochemical hub. It regulates our metabolism, promotes digestion and detoxification and supports immunity by producing and distributing proteins to prevent infections and ensure blood-clotting. It also directs cholesterol and hormones to the rest of our body, and helps maintain our energy balance, in addition to performing other functions.

The liver manages our energy by processing proteins, carbohydrates and fats into nutrients that the body can use. Liver cells produce bile – about 1,000ml per day – to ensure fat is broken down and absorbed. These cells also break down waste products such as drugs, alcohol, caffeine and toxins (both environmental and internal), converting them into substances that can be safely eliminated.

The food, medication and toxic substances we ingest and produce make their way through the bloodstream from our digestive organs to our liver through the portal vein. The liver acts as a filtration system, processing, modifying, detoxifying and/or storing these substances, which are then released into the blood or sent to the bowel for elimination.

The liver also acts as a storage hub when metabolising carbohydrates by safeguarding sugar molecules as glycogen, which helps to ensure glycaemic control. If your blood glucose levels are low, your liver can break down stored glycogen and release sugar into the blood. And in the reverse scenario, if your blood sugar levels are raised, your liver can remove the sugar and store it once again as glycogen. The liver can also convert glucose into fatty acids or amino acids.

Fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K) and minerals such as iron and copper are also stored in the liver and are released into the bloodstream when required.

Toxin exposure

We often think about detoxification before a big event, in the run-up to summer escapes, but perhaps mostly at the start of the New Year to cleanse the holiday over-indulgence following weeks of eating, drinking and festivities.

The reality is, our bodies are performing detoxification processes every day, all the time. We are amazing detoxification machines – in fact, that is one of the key purposes of the liver with assistance from other organs such as the kidneys, skin and lymphatic system.

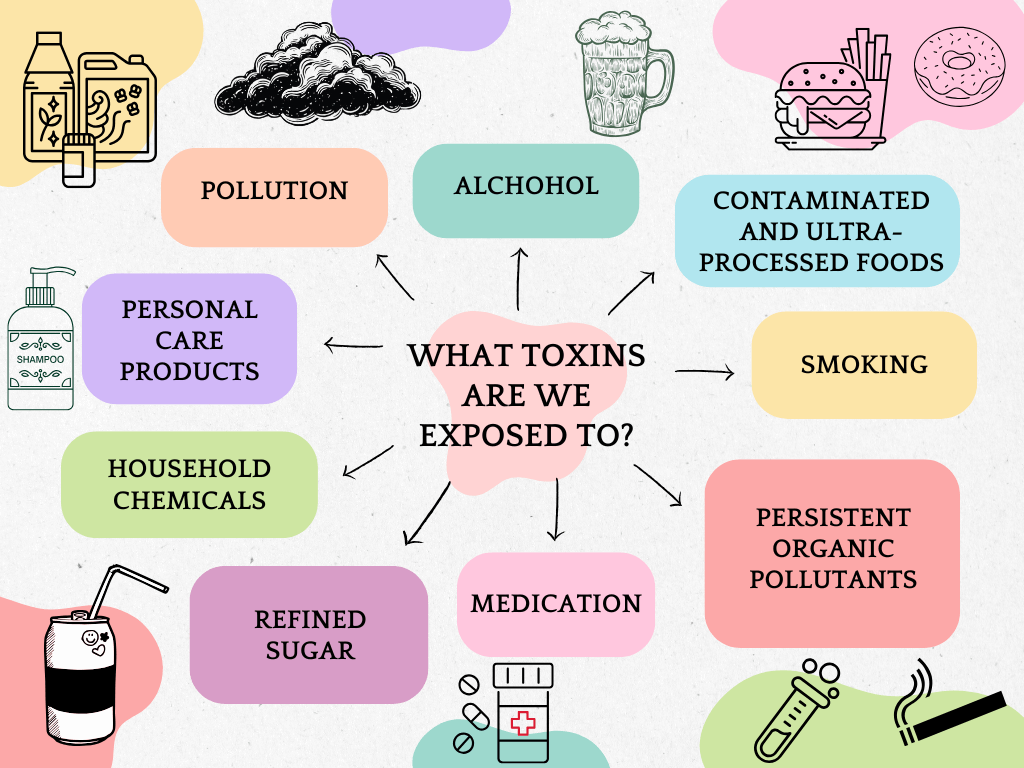

Toxins come from many different places; from polluted air, contaminated food and water, mould, plastics, pesticides, heavy metals, industrial and household chemicals, cosmetics, hair dye, medications and more.

What we choose to consume can also be toxic. Common dietary toxins include alcohol, and substances that are found in highly processed foods such as fructose and added sugars, trans fats, additives, and preservatives, which all place a burden on the liver.

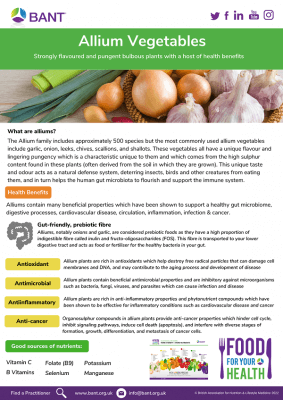

As is well known, regular consumption of highly processed foods can contribute to a disturbed gut, damaging the intestinal barrier and increasing dysbiosis. This is an example of an endotoxin – a component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria which is released when a cell disintegrates. In addition to exotoxins – from the environment and our food, the liver must also try to process, break down and flush endotoxins out of our systems. A leaky gut can end up passing large amounts of endotoxin to the liver through the portal vein, contributing to chronic inflammation and progressive liver damage.[3]

Once this cocktail of toxins has found its way into our bodies, we cannot get rid of it immediately. It is the liver’s job to first transform and convert the toxins into harmless substances before they can be released.

Detoxification pathways

The first phase of liver detoxification oxidises, reduces and hydrolyses toxins using a group of enzymes called cytochrome P450. These enzymes break down fat-soluble toxins such as pollutants, alcohol and medication into water-soluble forms that can be eliminated. [4] It is important to note that the metabolites created during this stage through oxidation, serve to make the toxins more chemically reactive and potentially more toxic than their original form.[5]

This is why antioxidants are so important to include in our diet as they can protect the body from damage at this stage. Kiwis, citrus fruits, bell peppers and other fruit and veg rich in vitamin C can work as antioxidants to neutralize free radicals generated during detoxification. Berries and green tea can reduce oxidative stress while B vitamins can support enzyme function and methylation.

The second phase is critical as this is where toxins are made safe. The liver conjugates the toxins to glutathione, amino acids or sulphur to make them water-soluble so they can be transported and excreted safely.

The liver needs a vast amount of ingredients for phase II to work quickly and efficiently. These include antioxidants; amino acids such as glycine, taurine, methionine and cysteine (found in eggs, salmon, lamb, beef, turkey, chicken, mung beans, spirulina, pumpkin seeds and lentils); B vitamins; magnesium (found in dark green leafy veg, nuts, seeds, beans and wholegrains), zinc, selenium and copper. Glutathione is supported by sulphur-rich foods like cruciferous vegetables, onions and garlic.[6]

The third phase is all about transportation and elimination. This is the part where toxins are flushed out of your system via your stool, urine and sweat. Fibre (in vegetables, fruits, lentils and wholegrains) is so important for this stage to work properly because it binds to toxins and contributes to regular bowel movements. Hydration is also key to ensure water-soluble toxins can escape through the urine, as is exercise, which promotes toxin release through sweat.

What impairs liver function and detoxification?

By understanding the different phases of detoxification, it is easy to see how a sedentary lifestyle, highly processed diet that results in chronic constipation, and a lack of water can all contribute to a damaged liver and impaired detoxification. With no way to exit, the toxins remain trapped and continue circulating in your body.

Besides toxin accumulation, viral hepatitis (particularly B and C), alcohol, drugs, a poor diet, obesity and type II diabetes, among other factors, can hamper liver function, leading to acute or chronic injury that may progress to fatal liver diseases.

Excessive alcohol consumption over a long period creates a clear pathway towards serious liver disorders. Heavy drinking causes the liver to become inflamed and swollen and can begin to destroy liver cells. Regular and excessive drinking can result in fat accumulation in the liver, leading to fatty liver disease, alcoholic hepatitis, and eventually cirrhosis. This can permanently damage the liver and cause liver cancer.

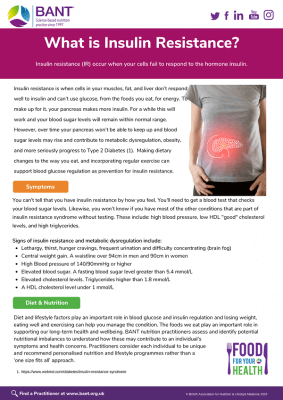

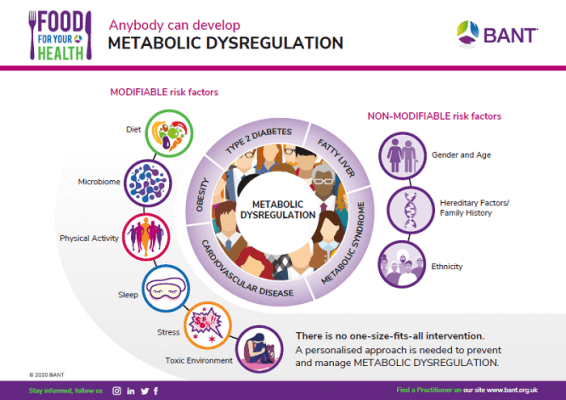

The contribution of metabolic syndrome to the pathogenesis of liver disorders such as MAFLD is a major concern from a nutritional therapy perspective. Metabolic syndrome consists of a combination of various conditions including obesity (especially excess visceral fat around the abdomen), hypertension, insulin resistance and type II diabetes, and dyslipidemia – abnormal blood levels of cholesterol and triglycerides. Conventional Western diets high in fat, sugar and salt have a huge role to play in the onset of all these conditions.

The impact of metabolic syndrome on liver health has huge implications for post-menopausal women, who have a higher risk of developing fatty liver disease and MASLD. The prognosis is worse for women who experience menopause before the age of 50, and particularly before the age of 45, according to research from the Hadassah Medical Centre and The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Following a study of 89,474 women, they established that women experiencing menopause between 40-44, had a 46% higher risk of fatty liver disease one year after menopause. In addition, early menopause was linked to an 11% increased likelihood of pre-diabetes and obesity, a 14% increased risk of hypertension, and a 13% increased risk of dyslipidaemia. For women aged 45-49 who entered menopause, the figures were a 30% higher risk of fatty liver disease and a 16% higher risk of pre-diabetes.[7]

Diet and lifestyle choices are fundamentally important in each of these cases given that metabolic syndrome results from excess calorie consumption that is disproportionate to metabolic requirements. Such changes often serve as the first line of therapy to prevent or delay the onset of symptoms and improve existing conditions.[8]

How do epigenetic factors affect liver health?

Epigenetic factors consist of regulatory factors that influence gene expression (without altering the DNA sequence) in response to environmental cues. In the liver, these changes play a crucial role in regulating metabolism, detoxification, and overall liver function.

A 2008 study analysed liver samples from 427 individuals to understand how genetic and epigenetic factors influence gene expression in the liver. Researchers used advanced techniques to examine over 40,000 gene transcripts and more than a million genetic markers. They discovered that many genes in the liver are controlled by specific regions of DNA that act like switches, turning genes on or off depending on various factors, including environmental influences like diet, toxins, and lifestyle.[9]

These epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, can affect how the liver processes fats, sugars, drugs and alcohol. Disruptions in these processes can be linked to the initiation and progression of liver disorders and other common conditions such as obesity and type II diabetes. Scientists are now trying to develop treatment and prevention strategies for liver-related conditions through underlying gene regulation rather than just symptoms.[10][11]

In fact, a study published this year from Penn Nursing pinpointed how the PPP1R3B gene could tell the liver whether to store energy as glycogen (sugar) or triglycerides (fat). “Our research shows that PPP1R3B is like a control switch in the liver,” said lead researcher Kate Townsend Creasy. “It directs whether the liver stores energy for quick use in the form of glycogen or for longer-term storage as fat.”[12][13] Creasy said the changes they observed in how efficiently mice and cells with genetic manipulations of PPP1R3B could use either glucose or fat for energy, could help in developing nutrition approaches to tackle metabolic diseases based on individual genetics.

Dietary interventions – how to love your liver

By now, it should be clear that certain diet and lifestyle changes can positively influence liver health by modifying epigenetic mechanisms and gene expression.

Let’s start with sugar. A study published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation compared the effects of glucose and fructose on liver metabolism in mice. While both sugars increased certain gene expressions, fructose activated genes linked to fat production and impaired insulin signalling, while glucose improved insulin sensitivity.[14]

This evidence suggests that reducing fructose (commonly found in sweetened beverages, processed snacks and fast foods) may help maintain healthier liver gene expression.

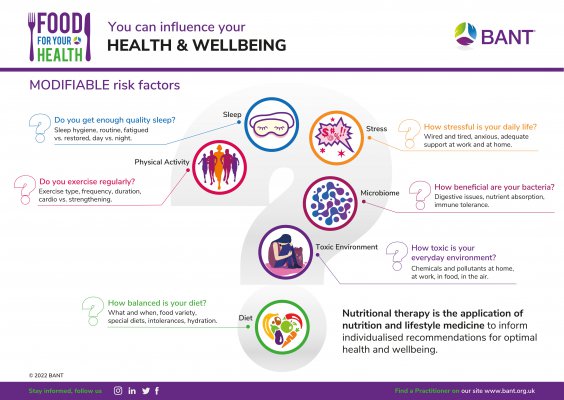

We’ve already discussed fibre and its role in promoting gut health, bowel regularity and toxin removal. Nutrient-dense whole foods including vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats help to reduce inflammation and thus ensure the liver functions optimally. The Mediterranean diet template has proven to help with weight loss and reduce inflammatory markers in patients with liver disease.[15]

Studies have shown that specific phytonutrients can help support the detoxification process by stimulating the liver to produce detoxification enzymes or by working in an antioxidant capacity to neutralize the negative effects of free radicals.[16] There is a also a growing list of herbs, spices and foods that can offer protection from oxidative stress, inflammation, gut dysbiosis, but also shield us from developing metabolic syndrome.[17]

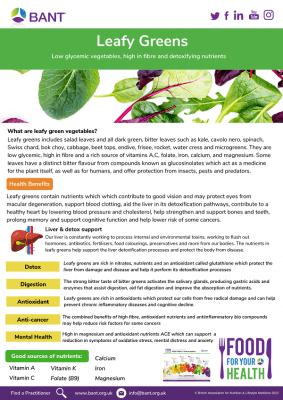

These include, but are not limited to:

Spices: Turmeric, cumin, cinnamon, cardamom and caraway seeds

Fruits: Grapes, mulberries, acai, cherries, oranges, watermelon, lemons, bananas and blueberries

Vegetables: Broccoli, onions, carrots, collard greens, kale, cabbage, yams, sweet potato

Grains: Barley, maize, brown rice, sorghum and oats

Healthy fats: Olive oil, oily fish (sardines, mackerel, anchovies, salmon and herring), avocados, flaxseeds, chia seeds

Teas: Green, black and dark varieties[18][19][20]

Lifestyle modifications can also go a long way in protecting the liver. Regular exercise has been shown to reverse harmful epigenetic changes associated with fatty liver disease and improve metabolic gene expression. A study of 96,688 participants using an accelerometer over a period of five and a half years showed a robust association between physical activity and protection from liver disease and its progression. Those in in the top quartile of physical activity had a 59% decreased risk of liver disease, a 61% lower risk of NAFLD development, and a 89% decrease in liver-related death development compared with those in the bottom quartile. An increase of 2,500 steps per day was associated with a 38% reduction in liver disease and a 47% reduction in NAFLD.[21]

Limiting environmental toxins is vital to reduce epigenetic disruptions too.[22][23][24] Think about investing in an air purifier if you live in a particularly polluted area and minimise your exposure to and ingestion of chemicals such as toxic hair dyes, deodorants, harsh cleaning products, smoking and alcohol. Eat organic where possible to reduce your consumption of pesticides.

Chronic stress can also alter gene expression through hormonal pathways. Think about incorporating mindfulness, sleep hygiene, and relaxation techniques help maintain epigenetic balance and overall liver health.

Author: Vandana Chatlani, BANT Registered Nutritionist ®

[1] Liver disease death rates quadruple in 50 years: Liver disease now among leading causes of death for working-age UK adults – British Liver Trust

[2] MASLD, NAFLD and fatty liver disease – British Liver Trust

[3] Endotoxins and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease – PMC

[4] Physiology, Liver – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf

[5] Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components: A Scientific Review with Clinical Application – PMC

[6] Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components: A Scientific Review with Clinical Application – PMC

[7] https://www.ihcan-mag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/june25.pdf

[8] Metabolic syndrome: pathophysiology, management, and modulation by natural compounds – PMC

[9] Mapping the Genetic Architecture of Gene Expression in Human Liver | PLOS Biology

[10] Mapping the Genetic Architecture of Gene Expression in Human Liver | PLOS Biology

[11] Epigenetic Effects of Ethanol on the Liver and Gastrointestinal System – PMC

[12] Scientists Discover Key Gene Impacts Liver Energy Storage, Affecting Metabolic Disease Risk • Home • Penn Nursing

[13] Ppp1r3b is a metabolic switch that shifts hepatic energy storage from lipid to glycogen – PMC

[14] Divergent effects of glucose and fructose on hepatic lipogenesis and insulin signaling – PMC

[15] Nutritional Support for Liver Diseases – PMC

[16] Guided Metabolic Detoxification Program Supports Phase II Detoxification Enzymes and Antioxidant Balance in Healthy Participants – PMC

[17] Metabolic syndrome: pathophysiology, management, and modulation by natural compounds – PMC

[18] Plant-Based Foods and Their Bioactive Compounds on Fatty Liver Disease: Effects, Mechanisms, and Clinical Application – PMC

[19] Plants Consumption and Liver Health – PMC

[20] Medicinal plants and bioactive natural compounds in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A clinical review – ScienceDirect

[21] Physical activity is associated with reduced risk of liver disease in the prospective UK Biobank cohort – PMC

[22] The exposome and liver disease – how environmental factors affect liver health – PMC

[23] Environmental Risk Factors Implicated in Liver Disease: A Mini-Review – PMC

[24] The dark side of beauty: an in-depth analysis of the health hazards and toxicological impact of synthetic cosmetics and personal care products – PMC